From behaviorism to humanism: Incorporating self-direction in learning concepts into the instructional design process. In H. B. Long & Associates, New ideas about self-directed learning. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education, University of Oklahoma, 1994 (Roger Hiemstra & Ralph Brockett) [figure no. shown do not reflect the actual publication]

Roger Hiemstra (Syracuse University) and Ralph G. Brockett (University of Tennessee)

Throughout our professional careers we have attempted to "practice what we preach" in terms of the way we work with adult learners. This has involved the incorporation of self-directed learning principles into our teaching, training, and volunteer work in various ways. Two of our basic premises are that (a) it is important to empower adults to take personal responsibility for their own learning, and (b) instructional activities should be based on learners' perceived needs. We recognize there are various levels of perceived needs ranging from felt needs or wants where the highest internal control may be possible to prescribed or externally mandated requirements where little internal control often is possible. However, it is our contention that even in situations where prescribed learning is the ultimate goal, the learning process will be enhanced if learners can perceive corresponding instruction as meeting individual needs or they can at least take some responsibility for aspects of the process.

We also have written about self-direction in learning and how what is known about this topic can be used to individualize the instructional process (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1991; Hiemstra & Sisco, 1990). In addition, a number of our students have completed doctoral dissertations that have in some way focussed on efforts to understand the value of adults taking more responsibility for directing their own learning efforts.

However, we have found that many of our beliefs and actions run counter to the "expert" or directed instruction role assumed by some teachers, trainers, and administrators who work with adult learners. It is our observation that many people have difficulty accepting some of the humanistic philosophical underpinnings crucial for self-directed learning success. They may even accept certain humanistic beliefs but feel compelled to employ a more directed instructional approach because of organizational or traditional expectations about the teaching and learning process.

Regardless of who is involved or the philosophical framework at work, the design of instruction for adults normally involves an analysis of learning needs and goals and subsequent development of a delivery system or approach for meeting such needs. It includes such activities as developing learning materials, designing instructional activities, determining techniques for involving learners, facilitating learning activities, and carrying out some evaluation efforts.

However, to illustrate how the same instructional functions can be conceived of quite differently, two separate disciplines, adult education and instructional design, will be examined. Adult educators and instructional designers in university graduate training programs usually are in separate departments; but they often have many of the same goals, such as helping students become more adept for work in business and industry as training/HRD specialists. For example, currently at Syracuse University more than one-third of those students concentrating on graduate adult education are already trainers or will go into training/HRD positions. That percentage is above 50% for those students focussing solely on graduate work in instructional design. Similarly, at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, a large percentage of adult education graduate students are employed (or aspire to be employed) in training settings. Many of these students work with faculty in both Adult Education and Industrial Training; in fact, at Tennessee these two programs are even housed in the same department.

In both the institutions noted above (our respective institutions), faculty in the mentioned programs or departments are engaged in the design of instruction on almost a daily basis. Many students take courses in both areas and faculty often serve together on dissertation committees. Yet, there often are real differences between these two groups in the way the instructional process is viewed.

It appears that many adult educators today, especially those recognizing the value of self-direction in learning, operate primarily from humanist beliefs and considerable attention is given to maximizing the value of previous experience and the input learners can have in the instructional process. It should be noted, however, that much of adult education research in the 1960's and 70's was based on positivist paradigms and quantitative or scientific research methods (Merriam, 1991). Only during the past fifteen to twenty years has a more interpretive paradigm derived from humanism and phenomenology been used increasingly by adult educators where interactive instructional approaches and more qualitative research methods are employed (Marsick, 1988).

It also has been our observation that some instructional designers (and many other educators) seem to have difficulty accepting or incorporating humanist beliefs and instead appear guided primarily by behaviorist or neobehaviorist beliefs and paradigms based primarily on logical positivism, although cognitive psychology is increasingly informing the instructional design field. Some may accept many humanistic beliefs but work for organizations that require the employment of training approaches that are primarily behavioristic in nature. They often have strong technical capabilities in implementing instructional design models but many may not have adequate grounding in adult learning theory or knowledge. Instructional design writings pertaining to learning theory contain a body of literature that grows primarily from behavioral and cognitive psychology. Many such authors seem unaware of or unwilling to incorporate knowledge related to humanistic psychology and adult development, although in reality much of their focus is on educating youth or traditional undergraduate students.

To carry this illustration further, instructional design as a separate discipline, has developed from several forms of inquiry: (a) research pertaining to media usage and communications theory; (b) general systems theory and development; and (c) psychological and learning theory. Reigeluth (1983) suggests that the three theorists most responsible for the current development of instructional design knowledge include B. F. Skinner (1954), David Ausubel (1968), and Jerome Bruner (1966). Skinner is identified because of his work with behaviorism and Bruner and Ausubel are recognized because of their contributions to cognitive psychology. Reigeluth (1987) has also compiled information on several other authors, theories, and models he believes important to the development of instructional design as a profession. Gagne (1985), Piaget (1966), and Thorndike (and colleagues) (1928) are other scholars frequently cited as foundational for much of today's thinking about instructional design.

Adult education as a separate discipline or field of study also has developed from several lines of inquiry. For example, Merriam and Caffarella (1991) suggest that theory development pertaining to adult learning stems from considerable research on why adults participate in learning, general knowledge about the adult learner, and self-direction in learning (Cross, 1981; Tough, 1979). The body of research on adult characteristics, popular ideas pertaining to what Knowles (1980) calls andragogy, theories based on an adult's life situation, and theories pertaining to changes in consciousness or perspective (Mezirow, 1991) combine to provide the field's basis for designing instructional efforts.

We consider it important to understand why some of the philosophical differences between the two disciplines exist. Obviously, there is much adult educators can learn by reading instructional design and HRD literature, but the reverse is true, too. As Hollis (1991) notes, "traditionally, instructional technologists have largely ignored the humanists' ideas among all the available theories from which to draw upon and incorporate into their schemes. Theoretically, instructional technology has been based on research in human learning and communications theories. In reality, more borrowing of ideas is needed, especially from the ranks of the humanists" (p. 51). We suggest there is tremendous potential in meshing the two somewhat different philosophical points of view that appear to undergird the separate fields.

For example, we think instructional designers can become more effective in training trainers by increased understanding of what adult educators have to say on facilitating adult learning processes. We also believe that adult educators can learn much about the micro-design of instruction by becoming more familiar with instructional design approaches.

Furthermore, we anticipate that business and industry trainers will need to depend increasingly on self-directed involvement by employees in the future because of declining dollars available for training. The enhanced understanding of self-directed learning principles that has been garnered from research reported in various sources (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1991; Candy, 1991; Confessore & Long, 1992; Long & Associates, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992; Long & Confessore, 1992; Long & Redding, 1991) and the impact of an annual International Symposium on Self-Directed Learning has very real implications for the way educators should work with adults. This means that the self-directed learning knowledge emanating primarily from adult educators during the past two decades has considerable potential in the future design of instructional efforts.

Thus, the purpose of this chapter is to promote a better understanding of why some educators and trainers of adults do not incorporate self-directed learning concepts in their practice. We expect that such understanding will help adult educators be more convincing in promoting self-direction in learning and corresponding implementation recommendations.

BASIC ELEMENTS OF HUMANIST THOUGHT

As we noted above, our conceptions of self-direction in adult learning are derived largely from a foundation of humanism. The roots of modern humanist thought can be traced to the ideas of such individuals as the Chinese philosopher Confucius, Greek philosophers such as Progagoras and Aristotle, Erasmus and Montaigne from the Renaissance period, and the Dutch philosopher Spinoza from the seventeenth century (Elias & Merriam, 1980; Lamont, 1965).

Humanism generally is associated with beliefs about freedom and autonomy and notions that "human beings are capable of making significant personal choices within the constraints imposed by heredity, personal history, and environment" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 118). Humanist principles stress the importance of the individual and specific human needs. Among the major assumptions underlying humanism are the following: (a) human nature is inherently good; (b) individuals are free and autonomous, thus they are capable of making major personal choices; (c) human potential for growth and development is virtually unlimited; (d) self-concept plays an important role in growth and development; (e) individuals have an urge toward self-actualization; (f) reality is defined by each person; and (g) individuals have responsibility to both themselves and to others (Elias & Merriam, 1980).

Principles of humanist thought have served as a foundation for major developments in both psychology and education. In psychology, the humanist paradigm emerged as a response to both the determinism inherent in Freudian psychoanalysis and the limited place of affect and free will found in behaviorism. While many individuals have made important contributions to humanistic psychology, two of the most noteworthy contributors were Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers. Maslow (1970) discussed the concept of "self-actualization," which he described as "the full use and exploitation of talents, capacities, potentialities, etc." (p. 150). He identified a number of characteristics of self-actualizing people, three of which are tolerance for ambiguity, acceptance of self and others, and "peak experiences" that lead to personal transformation through new insights. Rogers (1961), through the approach he referred to as "client-centered therapy," noted that the major goal of therapy is to help clients foster greater self-direction. According to Rogers, self-direction "means that one chooses - and then learns from the consequences" (p. 171).

Humanistic education is based on similar ideas. Patterson (1973) has stated that "the purpose of education is to develop self-actualizing persons" (p. 22). According to Valett (1977), humanistic education is a lifelong process, the purpose of which "is to develop individuals who will be able to live joyous, humane, and meaningful lives" (p. 12). Priorities of humanistic education should include "[t]he development of emotive abilities, the shaping of affective desires, the fullest expression of aesthetic qualities, and the enhancement of powers of self-direction and control (emphasis added)" (p. 12). Essential characteristics of the humanistic educator are empathic understanding, respect or acceptance, and genuineness or authenticity (Patterson, 1973; Rogers, 1983).

Humanism is not without its critics. One of the most frequent criticisms, usually emanating from fundamentalists on the religious right, is that humanism runs contrary to basic tenets of Christian and other theological orientations. In fact, humanism does emphasize the "here and now" and frequently is viewed as denying existence of the supernatural, although as Elias and Merriam (1980) point out not all humanists see incompatibility between affirming autonomy and existence of a god. As Lamont puts it, "[h]umanism is the view-point that men [sic] have but one life to lead and should make the most of it in terms of creative work and happiness; . . . that in any case, the supernatural, usually conceived of in the form of heavenly gods or immortal heavens, does not exist" (1965, p. 14). While this assumption may dissuade some individuals from fully embracing humanism, we believe that teachers, trainers, or administrators do not have to abandon traditional theologies in order celebrate the good of humanity and to engage in practices designed to facilitate self-direction.

A second criticism is that humanism is sometimes believed to be a highly self-centered, or selfish, approach to life. Typically, the argument goes something like this: "If an individual is concerned primarily with personal growth and development, how can that person truly be concerned with what is good for all of society?" Humanists are quick to refute this misunderstanding. Lamont (1965), for instance, states that the individual can find one's "highest good in working for the good of all" (p. 15). Similarly, one of the characteristics of self-actualizers discussed by Maslow (1970) is the tendency for individuals to focus on problems that lie outside of themselves. Within the realm of adult education, one of the most powerful reflections of how humanists look at the relationship between individual and social concerns is offered in this observation made by Lindeman in 1926: "Adult education will become an agency of progress if its short-time goal of self-improvement can be made compatible with a long-time, experimental but resolute policy of changing the social order" (Lindeman, 1988, p. 105).

COMPARING THE TWO PHILOSOPHIES

We reviewed several sources, including our own previous work (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1991) and that of Merriam and Caffarella (1991), to make some comparisons between the philosophical beliefs of and instructional procedures used by adult educators and instructional designers. In some ways the results represent a continuum between humanist and behaviorist views. We cover an extensive time range, too, starting from Plato and Aristotle and continuing forward until very recent attempts at research on adult learning and cognitive psychology. Table1 displays the comparative information.

TABLE 1: COMPARISON OF KEY DIFFERENCES IN BELIEFS AND APPROACHES BETWEEN ADULT EDUCATION AND INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN?

| Adult Education Humanism Views | -vs- | Instructional Design Behaviorism Views |

| Plato | -vs- | Aristotle |

| Rationalism/emotionalism | -vs- | Empiricism |

| Reflection | -vs- | Sensory impression |

| Gestalt psychology | -vs- | Behavioral psychology |

| Search for whole patterns | -vs- | Search for single events or parts |

| Information processing | -vs- | Information acquisition |

| Separation of mind and body | -vs- | Innate mental abilities |

| Right brain hemisphere | -vs- | Left brain hemisphere |

| Memory | -vs- | Accumulation of knowledge |

| Learning how to learn | -vs- | Acquiring knowledge |

| Learning as a process | -vs- | Learning as an end product |

| Instruction as a process | -vs- | Instruction broken into manageable parts |

| Meaningful learning | -vs- | Rote learning |

| S - O - R (O = human organism) | -vs- | S - R |

| Dynamic view | -vs- | Mechanistic view |

| Perceptions | -vs- | Observable behavior |

| Internal thoughts | -vs- | Behavioral change |

| Liberal studies for adults | -vs- | Programmed learning |

| Maslow/Rogers | -vs- | Skinner/Thorndike |

| Cross/Knowles/Mezirow/Tough | -vs- | Ausubel/Bruner/Gagne/Piaget |

| Individual determines learning | -vs- | Environment shapes learning |

| Individual locus of control | -vs- | External locus of control |

| Personal control and evaluation | -vs- | Imitating and observing others |

| Role of experience | -vs- | Reinforcement/operant conditioning |

| Interactive needs assessment | -vs- | Task analysis |

| Facilitator | -vs- | Trainer |

| Qualitative methods predominate | -vs- | Quantitative methods predominate |

| Process evaluation | -vs- | Product evaluation |

| Goal free evaluation | -vs- | Criterion/normative/goal referenced evaluation |

| Learner controlled verification | -vs- | External testing |

| Affective learning | -vs- | Cognitive/mechanistic/psychomotor learning |

| Individuals control own destiny | -vs- | Predetermination |

| Andragogy | -vs- | Pedagogy |

| Self-directed learning | -vs- | Expert directs learning/expert models |

| Crystallized intelligence | -vs- | Fluid intelligence |

| Internal motivation | -vs- | External motivation |

| Relative ends | -vs- | Fixed ends |

Presenting comparisons in a dichotomous manner is always difficult because ideas, attitudes, and movements seldom fall neatly into an either-or configuration. There usually are various ways ideas or statements can be viewed and the interpretations we have made regarding the views of others may not reflect their reality. Establishing one side or view of the world versus another side or view can create unexpected or undesired emotions, too.

It is even difficult to say that many of the items presented in the comparison are "absolutely" attached to one side or the other. There is some overlap, some items may fit both sides, and some comparisons may be better understood as representations of representations of continua rather than dichotomies. There is even considerable debate in the literature as to how definitive the related research and thinking has been on some of the items. For example, right -vs- left brain hemispheric and crystallized -vs- fluid intelligence research both have been discussed and critiqued in various ways. So, Table1 should be viewed in light of these possible limits.

The instructional design field during the past decade also has become increasingly involved with cognitive science and psychology, producing considerable information on learning analysis and cognitive strategies (Gagne, Briggs, & Wager, 1992). Many researchers in cognition have sought to move beyond the strictures of any behaviorist schools of thought in various ways: (a) attempting to understand the physical makeup of human memory; (b) trying to discern the way information is stored, coded, and utilized by the human brain; (c) researching properties of short term memory; and (d) considering the needs, desires, emotions, attitudes, motivations, and values of learners in terms of cognitive change. Some scholars refer to instructional design based on cognitive assumptions and the structuring of knowledge as second generation instructional design theory (Merrill, 1991), although Duffy and Jonassen (1991) suggest that both behaviorism and cognitive psychology are girded by objectivist epistemologies where structured knowledge rather than a learner's experience or need is a basis for instruction.

Some of the current instructional design theories reflect changing views of how to work with learners most effectively. For example, Merrill's (1983) component display theory draws from the multiple perspectives of behavioral, cognitive, and humanistic beliefs. Likewise, Reigeluth's (1987) elaboration theory of instruction incorporates a great deal of learner control into the instructional design process.

Currently, debates within the instructional design field are also going on pertaining to the desires of some to recast the field in terms of constructionist views. Constructivism makes a decidedly different set of assumptions about learning and corresponding instruction. It is concerned with the way people construct knowledge based on experiences, mental structures, and beliefs (Jonassen, 1991). In essence, this means learners build their own meaning from new knowledge rather than having that meaning built by someone else. Instruction is then based on past experience and aims to develop a learner's skill at constructing meaning from new knowledge and experiences. Both the May and September, 1991, issues of Educational Technology are devoted to pro and con discussions of constructivism.

Thus, the complementary roles of experience, feeling, and cognition in learning are impacting on the ways instructional designers think about their tasks. Many of the views may no longer fit neatly into Table 1's right column descriptors

Adult education, too, has undergone several changes in the past two decades in addition to considerable scholarship on adult learning, self-direction, and instruction described earlier. Brookfield (1989) and Mezirow (1991; Mezirow & Associates, 1991) have been two of the scholars helping the field become more aware of critical thinking, transformative dimensions of adult learning, and emancipatory learning. Jarvis (1985) has encouraged adult educators to better understand sociological perspectives pertaining to the teaching and learning process. Smith (1982; Smith & Associates, 1990) has been instrumental in helping educators of adults understand more about learning how to learn concepts. Peters, Jarvis, and Associates (1991) even describe how the field's development in the past two decades has been informed by various interdisciplinary dimensions. All of these changes do not always fit neatly within the humanistic side of the comparison figure.

However, we have initiated this comparison as a mechanism to suggest that many adult educators and instructional designers (and even educators who devote most of their research and energy toward the education of youth) have been approaching several of the problems pertaining to learning and instruction from different ideological points of view and often different research methodologies. It is our contention that many of the tenets, beliefs, and views of the world that may appear to fit when dealing with youth or young adults with few life experiences may not work well for educators working with adults as learners.

HUMANIZING THE INSTRUCTIONAL PROCESS: APPLYING SELF-DIRECTION IN LEARNING PRINCIPLES

In the previous section, we made some general comparisons between what is often found in the fields of adult education and instructional development. Our intent was not to dichotomize the two fields into a right -vs- wrong status, nor did we intend to enter into what Tobias (1991) calls a perennial controversy between advocates of tailoring instruction to learners' unique attributes versus instruction that steers learners toward certain curricular standards. Rather, our goals was to show that although there are differences in the concepts and people representing the two fields, there is nonetheless much potential for exchange. There are several shared elements between the humanist orientation and the behaviorist paradigm:

Several years ago, Miller and Hotes (1982) presented a series of strategies for humanizing the systems approach to individual instruction. While stressing the use of "accurate measurable behavioral objectives," "appropriate practice opportunities," and "task analysis," Miller and Hotes pointed out that one way to humanize the system "is to make it responsive to the needs of the individual student" (p. 22). They believe the three strategies that can be useful are learning by example (modeling), learning by doing, and positive reinforcement. We believe there is considerable value in examining the ways humanist and behaviorist approaches to adult learning might be linked.

In our own work on self-direction in learning, we have presented a framework for understanding key dimensions of the concept (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1991). We developed what we call the Personal Responsibility Orientation (PRO) model (see Figure 1). This model starts with the notion of personal responsibility, in which "individuals assume ownership for their own thoughts and actions" (p. 26). This, we believe, is central to an understanding of self-direction in learning, especially when working with adults as learners. We assert that only by assuming primary responsibility for personal learning is it possible for an adult to take a proactive approach to the teaching-learning process. Obviously, we believe that an adult learner's proactivity is desirous because from our experiences the ability to be self-directed regarding learning pursuits benefits everyone. Further, personal responsibility is not an either/or characteristic; rather it exists within each of us to a greater or lesser degree.

FIGURE 1: THE "PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY ORIENTATION" (PRO) MODEL

In essence, we suggest that a humanistic orientation to the instructional process can help learners increase their levels of responsibility. We do recognize there may be times when self-directed opportunities are minimal, such as when involved in collaborative learning or when learning entirely new content, but believe that the assumption of personal responsibility is possible in ways not tied to the type of learning or content. We also recognize that various social, political, and organizational factors may inhibit the employment of humanistic techniques, but urge that as much attention as possible be given to the potential of learners taking charge of their own learning.

For example, in the PRO model, we make an important distinction between "learner self-direction" and "self-directed learning." Learner self-direction refers to those characteristics within an individual "that predispose one toward taking primary responsibility for personal learning endeavors" (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1991, p. 29). It is probably best understood in terms of personality. To a great extent, the characteristics of learner self-direction are found in basic tenets of humanistic philosophy and psychology, such as those described earlier in this chapter.

Self-directed learning, in the PRO model, refers specifically to the teaching-learning process, and centers on the planning, implementation, and evaluation of learning activities where learners assume primary responsibility for the process. For purposes of the current discussion, we would like to elaborate a bit on this notion, as this is where it is possible for educators and trainers to actively implement strategies that will allow them to humanize the instructional process.

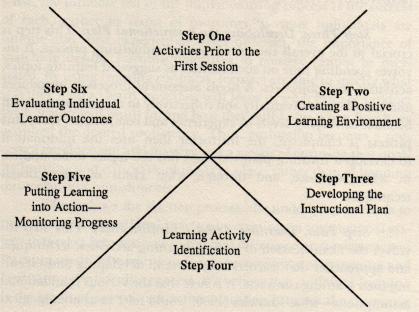

Both Patterson (1973) and Valett (1977) present a host of useful strategies designed to humanize education. While many of their ideas can be adapted to adult learning settings, these works tend to stress elementary and secondary education. More recently, Hiemstra and Sisco (1990) have presented an approach to individualizing instruction derived from principles of humanism and designed specifically for working with adult learners. The individualizing instruction (II) process model consists of six steps, which are related to each other in a circular rather than linear format (see Figure 2). The six steps are: (a) activities prior to the first session (e.g., developing a rationale, preplanning); (b) creating a positive learning environment (physical, social, and psychological); (c) developing the instructional plan (with active involvement of participants in assessing personal and relevant group needs, ascertaining the relevance of past experience, and prioritizing knowledge areas to be covered); (d) identifying the learning activities (determining learning activities and techniques); (e) putting learning into action and monitoring progress (formative evaluation); and (f) evaluating individual learning outcomes (matching learning objectives to mastery). In the II process, the instructor's role is to manage and facilitate the learning process; "optimum learning is the result of careful interactive planning between the instructor and the individual learners" (pp. 47-48).

FIGURE 2: INDIVIDUALIZING INSTRUCTIONAL PROCESS MODEL

In examining the II process model, it is not difficult to see some links between this humanist-derived approach and behaviorist-oriented models of systematic instructional design, stemming initially from Tyler (1950) and appearing in some aspects of several instructional theories portrayed by Reigeluth (1987) and his colleagues. For example, both the II model and most systematic or prescriptive instructional development models use an organized and deliberate design. Most stress the importance of the learning environment and all emphasize the need to evaluate learning.

At the same time, there are some very important differences between humanist and more behavioral approaches. For instance, an instructor in the II process serves more as a facilitator, while an instructor operating within a behavioral framework is more a manager or director of the process and delivery system. In addition, the II model places great importance on affective aspects of the teaching-learning transaction. Concern for interpersonal relationships and active involvement of learners in determining both process and content of the learning experience are two examples. Furthermore, while behaviorist models tend to focus on the outcomes of learning, the II approach also places great importance on "the process that enables mastery to occur" (Hiemstra & Sisco, 1990, p. 48).

One final element of the PRO model needs to be discussed. In the model, we stress the need to recognize the social and political context in which learning takes place. For example, while we believe that self-direction is vital to the teaching-learning process, we also recognize that the individualized emphasis of this approach may run contrary to values held in some cultural settings. In addition, there are times when the pragmatic requirements of a given training need may prevent learners from taking much or even any personal responsibility.

We do not wish to "impose" our approach on individuals or groups whose perceptions of reality (particularly with regard to individuality, autonomy, and personal responsibility) run contrary to ours; at the same time, we do feel obligated to share our views with such people to promote awareness of alternative ways of thinking and acting. It also is not our wish to seem like evangelists trying to convert others to a particular way of thinking. Rather, based on our experiences and knowledge bases, we believe in promoting learner self-direction as the most appropriate instructional approach when working with adults as learners.

UNDERSTANDING EACH OTHER

How do we move from ideas to action? It is our hope that this Chapter presents some ideas that will lead to discussion on how to help those from behaviorist or "teacher as expert" views see the humanist point of view and vice versa. As educators who have worked with colleagues from both the behaviorist and humanist perspectives, we believe that our backgrounds have been greatly enriched by exposure to both emphases. Yet, we are troubled by a perception that educators and trainers from both camps have limited exposure to each other's ideas. Our purpose in writing this chapter has been to share what we believe the humanist orientation has to offer educators and trainers who adhere to a more behaviorist orientation. At the same time, we believe it is equally important for educators who adhere primarily to behavioral or prescriptive learning views to share their own ideas on how to help humanist-oriented educators broaden their understanding.

Within the example of the two disciplines presented in this chapter, for example, we hope this will mean that adult education and instructional design faculty can dialogue with each other more frequently. In essence, we hope our message will help each side better understand and contribute to the other side so that our overall understanding about self-direction in learning and its role in the education of adults will be enhanced. For example, the micro-instruction skills of most instructional designers related to such activities as task analysis, media selection, and determining strategies for teaching certain knowledge components, can be very instrumental in helping the self-directed learner make effective use of study time. A recent merger of adult education and instructional design at Syracuse University is one illustration of how such understanding may lead to a blending of the best of both disciplines into some type of new whole.

We also are trying to find ways for better making the humanist case so those who believe primarily in behaviorism don't discount humanism. We feel very strongly that self-direction in learning, or the creation of self-directed learners as perhaps a better way of putting it, will be crucial for meeting many of the future training and continuing education needs. In fact, much of the literature pertaining to self-directed learning has demonstrated that adults prefer to take responsibility for their own learning if given appropriate opportunities (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1991). The increasing use of computer technology for individualized instruction and for distance learning is further reason for humanists, constructionists, and behaviorists to learn from each other (Hollis, 1991; Rieber, 1992). At Syracuse University, for example, humanistic, self-directed learning activities are important components of many of our computer mediated conferencing distance education courses (Hiemstra, 1991). As humanism, in our view, undergirds much of the understanding about self-direction, it is important that such a case be made.

Here are some initial ideas for those adhering to humanist views on how to promote a better understanding:

We take great pride in the humanist foundation that undergirds the way in which we practice. Humanism embraces the goodness of humanity and the virtual limitlessness of human potential. Self-direction is one of many ideas from educational practice that is tied to these basic values. We hope this chapter will prompt many readers to critically examine the ideas presented in light of their own philosophical underpinnings. We hope, too, that others will engage in dialogue through their own scholarship to help us move forward even further in pushing back the limits of knowledge in this vital area.

REFERENCES

Ausubel, D. P. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Brockett, R. G., & Hiemstra, R. (1991). Self-direction in learning: Perspectives on theory, research, and practice. New York: Routledge. [On-line]. Available: /sdlindex.html

Brookfield, S. D. (1989). Developing critical thinkers: Challenging adults to explore alternative ways of thinking and acting. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. New York: W. W. Norton.

Candy, P. C. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Confessore, G. J., & Long, H. B. (1992). Abstracts of literature in self-directed learning: 1983-1991. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Cross, K. P. (1981). Adults as learners: Increasing participation and facilitating Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Duffy, T. M., & Jonassen, D. H. (1991). Constructivism: New implications for instructional technology? Educational Technology, 31(5), 7-12.

Elias, J. L., & Merriam, S. (1980). Philosophical foundations of adult education. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Gagne, R. (1985). The conditions of learning (4th Edition). New York: Hold, Rinehart & Winston.

Gagne, R. M., Briggs, L. J., & Wager, W. W. (1992). Principles of instructional design (4th Edition). San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, and Jovanovich.

Hiemstra, R. (1988). Translating personal values and philosophy into practical action. In R. G. Brockett (Ed.), Ethical issues in adult education. New York: Teachers College Press. [On-line]. Available: /philchap.html

Hiemstra, R. (1994). Computerized distance education: The role for facilitators. MPAEA Journal of Adult Education, 22(2), 11-23. [On-line]. Available: /mpaea.html

Hiemstra, R., & Sisco, B. (1990). Individualizing instruction for adult learners: Making learning personal, powerful, and successful. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [On-line]. Available: /iiindex.html

Hollis, W. F. (1991). Humanistic learning theory and instructional technology: Is reconciliation possible? Educational Technology, 31(11), 49-53.

Jonassen, D. H. (1991). Evaluating constructivistic learning. Educational Technology, 31(9), 28-33.

Jarvis, P. (1985). The sociology of adult & continuing education. London: Croom Helm.

Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education (revised and updated). Chicago: Association Press (originally published in 1970).

Lamont, C. (1965). The philosophy of humanism (5th Edition). New York: Frederick Unger Publishing Co.

Lindeman, E. C. (1988). The meaning of adult education. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education (originally published in 1926).

Long, H. B., & Associates. (1987). Self-directed learning: Application & theory. Athens, GA: Adult Education Department, University of Georgia.

Long, H. B., & Associates. (1989). Self-directed learning: Emerging theory & practice. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Long, H. B., & Associates. (1990). Advances in research and practice in self-directed learning. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Long, H. B., & Associates. (1991). Self-directed learning: Consensus & conflict. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Long, H. B., & Associates. (1992). Self-directed learning: Application and research. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Long, H. B., & Confessore, G. J. (1992). Abstracts of literature in self-directed learning: 1966-1982. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Long, H. B., & Redding, T. R. (1991). Self-directed learning dissertation abstracts: 1966-1991. Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher Education.

Marsick, V. J. (1988). Learning in the workplace: The case for reflectivity and critical reflectivity. Adult Education Quarterly, 38, 187-198.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd Edition). New York: Harper & Row.

Merriam, S. B. (1991). How research produces knowledge. In J. M. Peters, P. Jarvis, & Associates, Adult education: Evolution and achievements in a developing field of study. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B., & Caffarella, R. S. (1991). Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive Guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merrill, M. D. (1983). Component display theory. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories and models: An overview of their current status. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Merrill, M. D. (1991). Constructivism and instructional design. Educational Technology, 31(5), 45-53.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J., & Associates. (1991). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Miller, B. W., & Hotes, R. W. (1982). Almost everything you always wanted to know about individualized instruction. Lifelong Learning: The Adult Years, 5(9), 20-23.

Patterson, C. H. (1973). Humanistic education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Piaget, J. (1966). Psychology of intelligence. Totowa, NJ: Littlefield, Adams.

Peters, J. M., Jarvis, P., & Associates. (1991). Adult education: Evolution and achievements in a developing field of study. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Rieber, L. P. (1992). Computer-based microworlds: A bridge between constructivism and direct instruction. Educational Technology Research and Development, 40(1), 93-106.

Reigeluth, C. M. (Ed.). (1983). Instructional-design theories and models: An overview of their current status. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Reigeluth, C. M. (Ed.). (1987). Instructional theories in action: Lessons illustrating selected theories and models. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1983). Freedom to learn for the 80's. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

Skinner, B. F. (1954). The science of learning and the art of teaching. Harvard Educational Review, 24(2), 86-97.

Smith, R. M. (1982). Learning how to learn: Applied theory for adults. Chicago: Follett Publishing Company.

Smith, R. M., & Associates. (1990). Learning to learn across the life span. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Thorndike, E. L., Bregman, E. O., Tilton, J. W., & Woodyard, E. (1928). Adult learning. New York: Macmillan.

Tobias, S. (1991). An eclectic examination of some issues in the constructivist-ISD controversy. Educational Technology, 31(9), 41-43.

Tough, A. M. (1979). The adult's learning projects (2nd ed.). Austin, Texas: Learning Concepts.

Tyler, R. W. (1950). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Valett, R. E. (1977). Humanistic education: Developing the total person. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby.

[See also the Self-Directed Learning Web page.]

______________

January 1, 2009

-- Return to guide to SDL papers page

-- Return to guide to SDL papers page