Self-Advocacy and Self-Directed

Learning:

A Potential Confluence for Enhanced

Personal Empowerment

Roger

Hiemstra, Professor Emeritus

Adult Education

Syracuse University

A Paper Presented at the

SUNY Empire State College Conference

“Disabled, But Enabled and Empowered”

March 20, 1998

Rochester, New York

Introduction

I am delighted to be here this morning. I believe this

conference is a very important one and applaud the efforts of Dr. Nancy Gadbow,

Dr. David DuBois, and all the many people who have been involved in its

planning and implementation. I am confident that many of the exciting ideas,

achievements, and sharing that are part of this conference will result in

outcomes of tremendous potential value to both disabled learners and those

educators working with disabled learners. I also wish to put in a plug for

Nancy and David’s 1998 book, Adult

Learners with Special Needs: Strategies and Resources for Postsecondary

Education and Workplace Training. I believe it to be a very important

contribution to those working directly or indirectly with disabled adults, and

I hope for disabled adults, themselves.

I’m going to begin my presentation with a long caveat. Like

a lot of adult educators my age, I have not been specially trained to work with

disabled adult learners. Nor do I have extensive experience working with or

knowledge of how to work with disabled adults. However, like most people who have

taught adults for more than 30 years, I have had disabled people in my

classrooms, including some with cognitive disabilities, physical disabilities,

and sensory disabilities. I’ve worked with a couple of students in the past

that had multiple disabilities and several that have had temporary special

needs.

If you are a caring individual, you learn how to make what

I would call common sense accommodations for learners who experience

difficulties or who have limitations. Gadbow and DuBois (1998) point out a

common myth that some teachers and educational administrators believe the

Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act

require accommodations that will be difficult to accomplish. In addition, I can

understand how learners with disabilities can feel a sense of educational

disadvantage (Preece, 1995). But I have found a simple common sense approach to

solving problems or listening to a disabled learner describe what is needed for

a successful experience goes a long way toward meeting needs. In addition, in

my own teaching I use a learning contract approach that enables each individual

learner to tailor learning activities to both personal needs and strengths. I

will talk more about my teaching and learning approach later in this

presentation.

Thus, because I do not have extensive experience related to

the topic of this conference, I approached the development of this presentation

like I do for most such efforts. I carried out some review of the literature

and, as I began outlining my presentation, I reflected on how aspects of what I

have been doing both practically as a teacher of adults and in my own

scholarship during the past 20 plus years supported what I could say. I’m

pleased to report that there appears to be a potential confluence or meeting

together of some streams of research or action that can support and build on

each other. In essence, I believe I have something to offer you today that can

at least stimulate some thought if not even ignite future collaborative

research and scholarship that will benefit disabled adult learners.

I know, too, that I have more material here than can be

covered during my allotted time. Thus, the full text of this presentation is

now on my web page. I also would be happy to send you a copy of my remarks

electronically as an email attachment.

The Potential Confluence

Gadbow and DuBois (1998) open their book with the following

statement:

Of the more than 49 million Americans

with disabilities (Bureau of Census, 1994), a large majority of those who are

adults under the age of 65 have the intellectual capability to learn at the

postsecondary level and the desire to be employed in meaningful work (Beziat,

1990). (p. 1)

They

continue by describing the reasons many such people have not participated in

educational programs, such as negative self-perceptions or various

institutional hurdles they face. Such students may also have had prior bad

experiences in certain educational institutions (Ashman & Elkins, 1990),

inadequate learning materials (Jacobowitz, 1990), or insufficient linguistic

skills (Whitman, 1990).

Fortunately, a few developments have

taken place to begin remedying some of these barriers. For example, the

self-advocacy movement that began in the 70’s has continued to grow until today

it encompasses more than 11,500 people in the United States and many more in

other countries. In essence, self-advocates are people with varying

disabilities who speak out on their own behalf concerning issues that directly

affect them.

As I read about the self-advocacy

movement and several related developments to provide background for this

presentation, increasingly I began to see areas of overlap with topics various

colleagues and I have studied over the past two or more decades. So for those

of you who like advanced organizers, here are two of those topics with which I

have been associated that I will address today:

¨

Self-direction in

Learning (in the literature most people refer to this as self-directed

learning)

¨

Individualizing

the Instructional Process

During

my discussion, I will suggest how a confluence of each topic with self-advocacy

as a vehicle for driving needed changes pertaining to the education of disabled

adults has potential value. I will conclude my presentation with some recommendations

for future action and invite any of you stimulated by my remarks to dialogue

with me electronically or via any other way.

However, before I dive into a

discussion of the first topic I wish to define a few terms to let you see my

level of awareness. This may help you better understand my later remarks. These

definitions are derived from my reading material in preparation for this

presentation. They are by no means intended to be definitive, as I may well

have missed important material.

The first of these, self-advocacy,

appears to stem primarily from a national organization devoted to enhancing

self-advocacy in the United States called SABE (Self-Advocates Becoming

Empowered). Perhaps some of you here today are involved with this organization.

I am not attempting here to talk about advocacy or the advocacy model that has

been developed in many ways through the social work field. Gadbow and DuBois

(1998) do discuss several related issues. However, in my view self-advocacy has

some very clear relationship to the concept of self-directed learning that I

will discuss in a few minutes.

¨

Self-advocacy –

the development of special skills and understandings that enable people to

explain their specific learning disabilities to others as a means of proactively

coping with prevailing attitudes (Lokerson, 1992).

This

concept of proactive assumption of responsibility is at the heart of much of

what we know about self-directed learning.

A separate but related concept is self-determination.

It appears primarily related to work of the Arc (formerly the Association for

Retarded Citizens of the United States). The stress of this group (again,

people involved with the Arc may be here today) is on the development of

self-determination for people with cognitive disabilities.

¨

Self-determination

– this refers to acting as the primary causal agent in one’s life and making

choices and decisions regarding one’s quality of life free from undue external

influence or interference (Wehmeyer, 1992).

It is

assumed here that people who are self-determined take control over and

participate in decisions that impact on their lives. Self-determined actions

reflect four essential characteristics: Autonomy, self-regulation,

psychological empowerment, and self-realization. All of these are related to

points I will make in describing self-directed learning and a process for

individualizing the instructional process.

One additional definition I’d like to handle here

deals with how each individual can be involved in the whole learning process.

In essence, my research during the past 25 years has convinced me that learning

how to learn is very important for any person (Smith & Associates, 1990). I

suspect this is especially important for any disabled adult who desires more

control over personal destiny.

¨

Metacognitive

learning – this involves competence in planning, monitoring, self-questioning,

and self-directing personal learning; in essence, this emphasizes actual

awareness of the cognitive processes that facilitate personal learning such as

self-determination or autonomy (Ashmore & Conway, 1993; Biggs & Moore,

1993 Lokerson, 1992).

The Center for People with Disabilities’ mission

statement expresses a belief that all people are entitled to the freedom to

make choices and the right to live independently (Center, 1997). This

humanistic view of personal empowerment and individual dignity, and I assume

this would extend to a concept like metacognitive learning, expresses an

optimistic perspective that celebrates each individual’s potential (Brockett,

1997).

Gadbow and DuBois (1998) eloquently talk about this

notion of individual potential:

Historically, the field of adult education has long

promoted the right of individuals to participate in educational programs “for

the sake of learning” itself as well as the right to participate in education

related to career and job needs. Not to encourage all adults who have the

capacity to learn to participate in learning activities that will help them

reach personal and professional goals goes against many of the basic

philosophical tenets long espoused by the field of adult and continuing

education. (p. 6)

As an adult and continuing educator, I truly believe

that the underlying philosophy of self-advocacy or self-determination is

consistent with what I know to be this prevailing adult education philosophy.

In essence, this provides an opportunity to apply adult learning theories and

what we know from practice to solving very real educational problems. In the

next two sections I shall offer some ideas on how such a confluence of views

and knowledge areas can enhance personal empowerment and the human potential of

everyone. I conclude with a section that contains several recommendations for

future action.

Self-Direction in Learning

I have been involved with

self-direction in learning in various ways for nearly 25 years. Personal

research and scholarship, supervising student research, and finding practical

ways of applying such research to adult teaching and learning are some of the

results. If you would like to read about much of this journey, I suggest

Brockett and Hiemstra (1991). Following is a brief description of the topic.

Most adults spend considerable time

acquiring information and learning new skills. The rapidity of change, the

continuous creation of new knowledge, and an ever-widening access to

information make such acquisitions necessary. Much of this learning takes place

at the learner's initiative, even if available through formal settings. A

common label given to such activity is self-directed learning. In essence,

self-directed learning is seen as any study form in which individuals have

primary responsibility for planning, implementing, and even evaluating the

effort. Most people, when asked, will proclaim a preference for assuming such

responsibility whenever possible.

Research, scholarship, and interest in

self-directed learning have literally exploded around the world in recent

years. Few topics, if any, have received more attention by adult educators than

self-directed learning. Related books, articles, monographs, conferences, and

symposia abound. In addition, numerous new programs, practices, and resources

for facilitating self-directed learning have been created. These include such

resources as learning contracts, self-help books, support groups,

open-university programs, electronic networking, and computer-assisted

learning.

Several things are known about

self-direction in learning: (a) individual learners can become empowered to

take increasingly more responsibility for various decisions associated with the

learning endeavor; (b) self-direction is best viewed as a continuum or

characteristic that exists to some degree in every person and learning

situation; (c) self-direction does not necessarily mean all learning will take

place in isolation from others; (d) self-directed learners appear able to

transfer learning, in terms of both knowledge and study skill, from one

situation to another; (e) self-directed study can involve various activities

and resources, such as self-guided reading, participation in study groups,

internships, electronic dialogues, and reflective writing activities; (f)

effective roles for teachers in self-directed learning are possible, such as

dialogue with learners, securing resources, evaluating outcomes, and promoting

critical thinking; (g) an increasing number of educational institutions are

finding ways to support self-directed study through open-learning programs,

individualized study options, non-traditional course offerings, distance

learning, and other innovative programs.

Self-directed learning has existed

even from classical antiquity. For example, self-study played an important part

in the lives of such Greek philosophers as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle.

Other historical examples of self-directed learners included Alexander the

Great, Caesar, Erasmus, and Descartes. Social conditions in Colonial America

and a corresponding lack of formal educational institutions necessitated that

many people learn on their own.

Early scholarly efforts to understand

self-directed learning took place some 150 years ago in the United States.

Craik (1840) documented and celebrated the self-education efforts of several

people. About this same time in Great Britain, Smiles (1859) published a book

entitled Self-Help, which applauded

the value of personal development.

However, it is during the last three

to four decades that self-directed learning has become a major research area.

Groundwork was laid through the observations of Houle (1961). He interviewed 22

adult learners and classified them into three categories based on reasons for

participation in learning: (a) goal-oriented people, who participate mainly to

achieve some end goal; (b) activity-oriented people, who participate for social

or fellowship reasons; and (c) learning-oriented people, who perceive of

learning as an end in itself. It is this latter group that resembles the

self-directed learner identified in subsequent research.

The first attempt to better understand

learning-oriented individuals was made by Tough, a Canadian researcher and one

of Houle's doctoral students. His dissertation effort to analyze self-directed

teaching activities and subsequent research in the early 1970’s with additional

subjects resulted in a book, The Adult's

Learning Projects (1979). This work has stimulated many similar studies

with various populations in various locations. One important finding among the

subjects studied has been the very large preference to control personal

learning and this led many educators of adults to talk about self-planned or

self-directed learning.

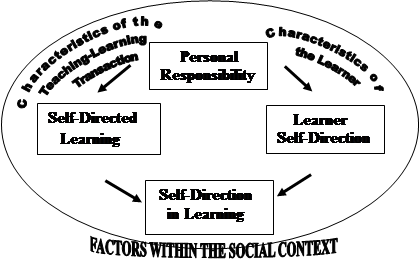

A

colleague and I (Brockett & Hiemstra, 1991) synthesized many aspects of the

knowledge about the topic and conceptualized the PRO (Personal Responsibility

Orientation) model. This model recognizes both differences and similarities

between self-directed learning as an instructional method and learner

self-direction, which is based on personality characteristics. As can be seen

in Figure 1, the point of departure for understanding self-direction is

personal responsibility and empowerment. Personal responsibility refers to

individuals assuming ownership for their own thoughts and actions. This does

not necessarily mean control over all personal life circumstances or

environmental conditions, but it does mean people can control how they respond

to situations.

Self-directed

learning, the left side of the model, refers to the actual teaching and

learning transactions, or what we refer to as those factors external to the

adult learner. Learner self-direction, the right side, refers to the personal

orientation of individuals engaged in a learning process. This involves a

learner’s personality characteristics, or those factors internal to the

individual such as self-concept.

Figure 1 The Personal Responsibility

Orientation (PRO) Model

In

terms of learning, it is an ability or willingness of individuals to take

control that determines any potential for self-direction. This means that

learners have choices about the directions they pursue. Along with this goes

responsibility for accepting any consequences of one's thoughts and actions as

a learner.

Brockett

and I view the term self-directed learning as an instructional process

centering on such activities as assessing needs, securing learning resources,

implementing learning activities, and evaluating learning. Another colleague

and I (Hiemstra & Sisco, 1990) refer to this as individualizing

instruction, a process focusing on characteristics of the teaching-learning

transaction, itself. I will address this process in the next section.

The PRO

model's final component is represented by the circle in Figure 1 that

encompasses all other elements. While the individual's personality

characteristics and the teaching and learning process are starting points for

understanding self-direction, the social context provides an arena in which the

learning activity or results are created. To fully understand self-directed

learning activity, the interface existing between individual learners, any

facilitator or learning resource, and appropriate social dimensions must be

recognized. Thus, Brockett and I recommend that self-direction in learning be

used as an umbrella definition recognizing those external factors facilitating

adults taking primary responsibility for learning and those internal factors or

personality characteristics that incline one toward personal empowerment or

accepting such responsibility.

Several

researchers also have demonstrated that giving responsibility back to learners

in many instances is more beneficial than other approaches. For example, in the

workplace employees with busy schedules can learn necessary skills at their own

convenience through self-study. Some technical staff in organizations who must

constantly upgrade their knowledge can access new information through an

individualized resource center.

Perhaps

most important of all, self-directed learning works! Many adults succeed as self-directed learners

when they could not if personal responsibility for learning decisions were not

possible. Some will even thrive in ways never thought possible when they learn

how to take personal responsibility and empower themselves for success as

learners. It is here that I believe the confluence of self-direction in

learning with self-advocacy, self-determination, or metacognitive learning has

the most potential.

In

working with learners from varying levels or types of disabilities, it may not

be possible to give carte blanche responsibility to each person. However, I

contend that there are many aspects of the entire teaching and learning process

where a person can take control and reap the personal benefits of learner

self-direction. To that end I have broken the teaching and learning process

down into various components in which learners can make their own decisions.

Thus, if it is not possible to make decisions about the actual content or any

learning activity, for example, it may be possible to assume responsibility for

the pace of the learning, the type of instructional technique used, or the manner

in which the learning processes are evaluated.

I also

am in the process of developing a resource guide of various instructional

techniques, tools, and resources that the self-directed learner or instructor

of self-directed learners can use in a learning endeavor. I have only begun the

process so it should be considered a work in progress. Both these efforts are

contained in an appendix to this presentation paper and I welcome your dialogue

if you access this paper and have thoughts, suggestions, or ideas on additional

material that I should include or areas I should consider changing.

Individualizing the Instructional Process

Growing out of this research on

self-directed learning was my desire to find practical ways of using such

knowledge in the instructional process. Linking the instructional process with

learner inputs, involvement, and decision making is crucial. I believe the

potential of humans as learners is maximized when there is a deliberate effort

by instructors to provide opportunities for participants to make decisions

regarding the learning process. The individualized instructional process that I

and Burt Sisco developed (1990) builds on the notion of individual

decision-making, the need for instructors to help learners become more self-directed,

and respect for adults because they do have so much untapped potential for

personal empowerment.

This approach involves learners in

determining personal needs and building appropriate learning situations to meet

those needs. It does so without imposing too many external controls or

instructor-directed biases. Sometimes learner needs and subsequent goals are

known early or can be determined quickly. Other times, such needs and goals may

be preset by an employer, stem from a specific content area requirement such a

college credit course, or arise because of some personal situation such as

dealing with a disability or coping with some aspect of living. There also are

instances when the learner needs some time or some type of process before

specific learning needs and goals surface.

In essence, the individualizing

process is based on a belief expressed in the previous section that all people

are capable of self-directed involvement in, personal commitment to, and

responsibility for learning. This includes making choices regarding

instructional approaches, educational resources, and evaluation techniques.

For teachers of adults the experience of

adapting all or some portions of the individualizing process can be a wrenching

one. It may mean giving up some beliefs about instructor or trainer roles.

Personality and institutional constraints may need examination and change. It

may require some tough examination of what is remembered about former teacher

role models. Frequently, many of our role models were traditional instructors

who used an approach quite contrary to an individualizing process. Thus, time

may be required before a teacher feels comfortable with some of the changes. It

most certainly will mean a reexamination of a personal philosophy about instruction

(Hiemstra, 1988; Hiemstra & Brockett, 1994). It may even necessitate some

real soul searching on whether or not some of our underlying assumptions about

people, whether disabled or not, can be accepted.

Thus, we developed a six-step process

for individualizing instruction in a way that learner inputs, involvement, and

decision-making are facilitated: (one) preplanning activities prior to meeting

learners, (two) creating a positive learning environment, (three) developing

instructional plans, (four) identifying appropriate learning activities, (five)

implementing and monitoring the instructional plan, and (six) evaluating

individual learner outcomes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Individualizing Instruction Model

Each step is sequential and designed to

help learners take increasing responsibility for their own learning. A key

ingredient of the model is the promotion of effective educational practice

through the creation of an instructional system that celebrates individual

differences, experiences, and learning needs. As Sisco (1997) notes,

By taking

advantage of the resident expertise so common in older, more mature learners,

the instructor can create optimum conditions for learning to occur. This is one

of the guiding principles in instructional design and certainly is a hallmark

of the Individualizing Instruction model. Understanding the instructional

process, being flexible and supportive when the need arises, helping learners

assume greater control of the learning process, and varying the instructional

methods and techniques so that active learning is emphasized all add up to

instructional success. (p. 399)

For

example, as I mentioned earlier, the process employs the learning contract

approach which enables a learner to design unique learning experiences to meet

personal needs with the guidance of a facilitator (Knowles, 1986). It also is

predicated on the notion that creating a positive learning environment takes

understanding and attention to adult needs (Hiemstra, 1991, 1997).

Success with the individualizing

instructional approach will depend on the attitude of anyone implementing it.

In other words, an instructor in a facilitator role will need to believe in the

overall potential of promoting self-direction in learning, accept learner

input, criticism, and independence, and seek a wide range of learning

resources. Learners, themselves, may need to overcome years of expectations

regarding the place or role of learners. This may require several efforts to

become more personally empowered. Changing approaches or attitudes toward

instruction or learning generally requires dedication, hard work, practice, and

time. However, I am convinced the effort is worth it and look forward to

dialogue with any of you on ways of applying the individualized instructional

process to adult learners with disabilities.

Recommendations

Following are a series of recommendations that come to

my mind after reflecting on the remarks I have made thus far. However, I

acknowledge that my insights are limited by my lack of experience and knowledge

about disabled adults. I invite further dialogue and suggested recommendations

from any of you.

1. I have suggested several ways self-direction in

learning and the individualized instructional process relate to aspects of

self-advocacy and self-determination. I further suggest there is potential in

the appendix material I presented for enhancing personal empowerment. However,

to determine their usefulness these ideas and materials should be scrutinized

by learners with disabilities and those educators who work with such learners.

2. The self-directed learning readiness and

metacognitive skills (learning to learn ability) of learners with disabilities

should be investigated and benchmarked to provide a baseline for further

development of the various ideas I presented (Boote, 1997).

3. Research should be conducted to determine the most

appropriate approaches to promoting learner self-direction for adults with

disabilities.

4. Research should be conducted to determine how best

to implement aspects of the individualized instructional process with adults

with disabilities.

5. Efforts should be made to find ways of increasing

the metacognitive (learning to learn) skills of adults with disabilities.

6. Programs of any sort designed to train educators

and trainers of adults should be better informed by researchers and

practitioners who have experience with disabled adults so that future research,

scholarship, and training efforts can be improved and made more inclusive in

nature.

7. A series of in-service training workshops should be

conducted with current teachers and trainers of adults to help them understand

the learning needs and potential of adults with disabilities. Information

emanating from conferences like this one can serve as a basis for such

training.

8. Research should be conducted to better understand

the potential and limitations of distance education technologies in reaching

adults with disabilities (Coombs, 1989; Rohfeld & Hiemstra, 1995; Willis,

1994).

9. Programs should be designed that will help disabled

adults enhance their ability to use self-directed learning techniques and

resources, such as learning contracts.

10. Scholars and practitioners working with

self-advocacy and self-determination efforts and those working with

self-direction in learning efforts should meet to discuss ways of working

together to meet the needs of disabled adults. We have much to learn from each

other.

Appendix

The following ideas and resource

materials are premised on ideas about empowering learners that have emanated

from some of the research on self‑directed learning. Much of this

research in North America during the past 25 years has demonstrated that most

adult learners prefer to take considerable responsibility for their own

learning. Yet, many traditional teaching and training situations limit

opportunities for such personal involvement because control over content or

process remains in the hands of experts, designers, or teachers who depend

primarily on didactic approaches.

One of the initial responses I made to

this apparent disparity between what such research has demonstrated and much of

current teaching or training practice was the development of the individualized

instructional process described above (Hiemstra & Sisco, 1990). In this

process it is suggested there are various ways learners can take responsibility

for their own learning without leading to anarchy in the learning setting.

Some of our critics suggest that the

process we advocate will not work with their particular teaching areas or

students because the content is controlled by organizational requirements, must

be taught in a particular sequence, or is too advanced for novice learners. We

contend that the process of providing opportunities for learners to assume some

control is equally as important, if not often more important, than the actual

content because of the ever declining half‑life of much of knowledge and

the value in helping learners learn how to learn.

What I have been wrestling with

recently is thinking through various ways that learners can assume increasing

control over certain aspects of their learning process, in other words become

more empowered. As noted earlier, I am in the process of developing two related

products. One is a framework for identifying various teaching and learning

process components in which learners can make their own decisions (Figure 3).

The following material outlines my thinking to date. The second product (Figure

4) is a resource guide of various techniques, tools, and resources that the

self-directed learner can use to plan personal learning efforts, enhance

personal skills, or obtain new knowledge. The framework represents a work in

progress, showing various techniques, tools, or resources displayed within six

categories. A few of them have initial descriptions to provide an idea of what

I hope to accomplish.

Thus far I have reviewed related

literature, talked to colleagues, reflected on my own teaching, and thought

about what such resources should look like if they are to be of value to

learners, themselves, or to those wishing to enhance the self-directed learning

skills of learners. This material most likely will not be very helpful to you

at this early point in its development, although it does give you an idea of

the kinds of resources that are possible. As you are one of the first groups of

people to see this evolving effort, I would very much appreciate any feedback

you care to give me. Does it make sense in the organizational scheme I am

suggesting? Are there some obvious things I am missing? Please feel free to

contact me with any of your feedback. I will be very grateful and your advice

will help me to make it a more useful resource.

Helping Learners Take Responsibility for Self-Directed

Activities

Roger Hiemstra

Research

has clearly demonstrated that adults prefer to assume some responsibility for

their own learning. However, some instructors and even some learners resist

this notion for various reasons. One of my current projects involves developing

a framework of teaching and learning process components to provide multiple

opportunities for learners to make their own decisions. The following

represents my work thus far. At each numbered item, a yes, no, or sometimes

question should be asked in terms of whether or not learners can assume

control.

1. Assessing Needs

1.1 Choice of individual techniques

1.2 Choice of group techniques

1.3 Controlling how needs information is

reported

1.4 Controlling how needs information is used

2. Setting goals

2.1 Specifying objectives

2.2 Determining the nature of the learning

2.2.1 Deciding on competency or mastery

learning -vs.- pleasure or interest learning

2.2.2 Deciding on the types of questions to be

asked and answered during learning efforts

2.2.3 Determining emphases to be placed on the

application of the knowledge or skill acquired

2.3 Changing ("evolution")

objectives over the period of a learning experience

2.4 Use of learning contracts

2.4.1 Making various learning choices or

selecting from various options

2.4.2 Decisions on how to achieve objectives

3. Specifying learning content

3.1 Decisions on adjusting levels of

difficulty

3.2 Controlling sequence of learning material

3.3 Choices on knowledge types (psychomotor,

cognition, affective)

3.4 Decision on theory -vs.- practice or

application

3.5 Deciding on level of competency

3.6 Decisions on actual content

3.6.1 Choices on financial or other costs

involved in the learning effort

3.6.2 Deciding on the help, resources, or

experiences required for the content

3.7 Prioritizing the learning content

3.8 Deciding on the major planning type, such

as self, other learners, experts, etc.

4. Pacing the learning

4.1 Amount of time devoted to teacher

presentations

4.2 Amount of time spent on teacher to learner

interactions

4.3 Amount of time spent on learner to learner

interactions

4.4 Amount of time spent on individualized

learning activities

4.5 Deciding on pace of movement through

learning experiences

4.6 Decisions on when to complete parts or all

of the activities

5. Choosing the instructional methods, techniques, and

devices

5.1 Selection of options for technological

support and instructional devices

5.2 Choice of instructional method or

technique

5.3 Type of learning resources to be used

5.4 Choice of learning modality (sight, sound,

touch, etc.) for determining how best to learn

5.5 Choices on opportunities for learners,

learner and teacher, small group, or large group discussion

6. Controlling the learning environment

6.1 Decision on manipulating

physical/environmental features

6.2 Deciding to deal with

emotional/psychological impediments

6.3 Choices on ways to confront

social/cultural barriers

6.4 Opportunities to match personal learning

style preferences with informational presentations

7. Promoting introspection, reflection, and critical

thinking

7.1 Deciding on means for interpreting theory

7.2 Choices on means for reporting/recording

critical reflections

7.3 Decision on use of reflective practitioner

techniques

7.4 Opportunities provided for practicing

decision-making, problem solving, and policy formulation

7.5 Making opportunities to seek clarity or to

clarify ideas available

7.6 Choices on practical ways to apply new

learnings

8. Instructor's/trainer's role

8.1 Choice of the role or nature of didactic

(lecturing) presentations

8.2 Choice of the role or nature of Socratic

(questioning) techniques to be used

8.3 Choice of the role or nature of

facilitative (guiding the learning process) procedures

9. Evaluating the learning

9.1 Choice on the use and type of testing

9.1.1 Deciding on the nature and use of any

reviewing

9.1.2 Opportunities for practice testing

available

9.1.3 Opportunities for retesting available

9.1.4 Opportunities available for choosing

type of testing, if any, to be used

9.1.5 Decisions on weight given to any test

results

9.2 Choices on type of feedback to be used

9.2.1 Deciding on type of instructor's

feedback to learner

9.2.2 Deciding on type of learner's feedback

to instructor

9.3 Choices on means for validating

achievements (learnings)

9.4 Deciding on nature of learning outcomes

9.4.1 Choosing type of final products

9.4.1.1 Deciding how evidence of learning is

reported or presented

9.4.1.2 Opportunities made available to revise

and resubmit final products

9.4.1.3 Decisions on the nature of any written

products

9.4.2 Decision on weight given to final

products

9.4.3 Deciding on level of practicality of

outcomes

9.4.3.1 Opportunities to relate learning to

employment/future employment

9.4.3.2 Opportunities to propose knowledge

application ideas

9.4.4 Deciding on nature of the benefits from

any learning

9.4.4.1 Opportunities to propose immediate

benefits versus long-term benefits

9.4.4.2 Opportunities to seek various types of

benefits or acquisition of new skills

9.5 Deciding on the nature of any follow-up

evaluation

9.5.1 Determining how knowledge can be

maintained over time

9.5.2 Determining how concepts are applied

9.5.3 Opportunities provided to review or redo

material

9.5.4 Follow-up or spin-off learning choices

9.6 Opportunities made available to exit

learning experience and return later if appropriate

9.7 Decision on the type of grading used or

completion rewards to be received

9.8 Choosing the nature of any evaluation of

instructor and learning experience

9.9 Choices on the use and/or type of learning

contracts

Figure 3. Aspects of the

Learning Process Where Learners Can Assume Some Control

A. Planning

Tools

A1. The Learning Contract

Plan/Learning Contract Design.

The learning contract is a device whereby you can plan and personalize any learning

experience. It can take on many shapes and forms ranging from audio tapes,

to outlines, to descriptive statements, to elaborate explanations of

process and product, to electronically submitted forms.

More examples can be found in O'Donnell, J. M., & Caffarella, R. S. (1990).

Learning contracts. In M. W. Galbraith (Ed.), Adult learning

methods: A guide for effective instruction (pp. 133-160). Malabar, FL: Krieger

Publishing Company. Most contracts contain information on your learning goals,

anticipated learning resources and strategies, a projected time line, and ideas

for how you will evaluate or validate your learning achievements.

A2. Self Diagnostic Form.

A self diagnostic form is an

instrument designed to assist you in assessing personal levels of competence

and need related to possible areas of study. Such information typically helps

in identifying and developing many of the professional competencies required to

understand a particular topic of interest or need and often is used as a precursor

to construction of a learning contract. Here is example one and example two from different graduate courses.

A3. Self Analysis as a Learner.

This involves you in carrying out

an analysis of yourself or others as a learner. It includes determining such

factors as the ways you learn best, developmental patterns or social roles

which impact on your learning efforts, subject areas which you like best, strengths

and weaknesses as a learner, and what, if any, you would change to improve your

learning performance. Several self-administered instruments are available for

your use if desired.

1. Competencies for performing life

roles

2. Self-directed learning skills

3. Competencies for carrying out

self-directed learning projects

A4. Self-Directed Learning Readiness

Scale.

A self-administered and

self-scored instrument entitled the Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale (SDLRS) is available for

comparison of yourself with normed information. An opportunity also is provided

for you to detail what the results means in terms of future learning approaches

and efforts.

A5.Self-Directed Learning Perception Scale (SDLPS).

A self-report instrument, to

monitor the support of a self-directed learning environment.

A6. Self Rating on Self-Directed

Learning Competencies.

A

self-administered and self-scored competency rating device is available for

obtaining information about self-directed learning abilities. An opportunity

also is provided for you to detail what the results means in terms of future

learning approaches and needed competency acquisitions.

This exercise

helps you gain an understanding of and practice with a self-diagnosis process.

A model of desired behaviors or required competencies pertaining to learning

about a particular topic is created and any gaps identified in current

competency levels becomes the basis for planning future learning.

A8. Analyzing Your Thinking Skills and

Intelligence Types.

You are introduced

to various thinking skill types and personal intelligence

types and the nature of the

information typically foundational to each type. A self-assessment of how your

thinking approaches and/or personal intelligence fit the various types is

determined and you can then determine some of the implications for your

future learning activities studied.

A9. Determining Your Learning Style.

Several

self-administered and self-scoring instruments are available to help identify your own learning

style. One or more of these can be completed and the resulting scores and

associated meanings used to think through implications and approaches for

subsequent learning efforts.

A10.

Determining Your Teaching Style.

The PALS ( Principles of Adult Learning Scale)

instrument is a device that measures the various things that a teacher or

trainer does when working with adult learners. You complete, self score the

instrument, and compare the results with some normed information to determine any

implications for future efforts to improve your teaching or training abilities.

Contact the instrument developer, Gary Conti, or you can find the

instrument and scoring information in Conti, G. J. (1990). Identifying your

teaching style. In M. W. Galbraith (Ed.), Adult learning

methods: A guide for effective instruction (pp. 79-96). Malabar, FL: Krieger

Publishing Company.

A11. Determining

Individual Change Styles.

The "Change

Styles Questionnaire" is an instrument developed to assess how an

individual's self-directed and problem solving approaches or preferences

coalesce to create various individual change styles. Knowledge about such styles

helps individuals and teachers or trainers find ways of dealing with learning

and changes in the workplace and other settings. See also a background paper on the instrument.

A11. Constructing

a Gantt Chart.

Critical Path

Analysis (CPA) and the creation of a Gantt Chart is a useful tool for planning,

scheduling, and managing various self-study activities. You are shown how to delineate

and sequence those activities necessary for carrying out a set of learning

objectives. The calendar dating of a CPA network and creation of a Gantt time

management chart are included in the process.

B. Individual

Study Techniques

B1. Mind Mapping/Concept Mapping.

Mind mapping is a

visually oriented technique designed to allow you to see or make connections

among widely disparate elements of some subject you are studying. You are shown

how to use interconnecting arrows, branching ideas, and personal patterns to expand

your knowledge about a particular topic. In this technique you also learn how

to develop mind or concept

mapsto pinpoint the various misconceptions or nuances of meaning that you

may hold so that your interpretation skills are increased.

Probes are ideas,

questions, and insights you develop while you are in the process of learning

something about a new topic or field. You learn how to use dialogue,

conversation, and questioning that turns learning something new from a passive

to an active process. Developing propositions and revised propositions become a

part of your learning repertory.

B3. Vee

Diagramming/Vee

Heuristic Technique.

The Vee

diagramming/heuristic technique is a problem solving aid in helping you see the

interplay between what you already know and knowledge you are producing or

attempting to understand. You learn how to use a Vee to point to events or

objects that serve as foundations for any knowledge being developed or learned.

B4. How

to Read a Journal/Magazine.

B5. Learning

from TV and Radio.

B6. Exercising.

An important means

for establishing your physiological state for individualized learning is to

carry out some brisk exercising. The World Wide Web has a multitude of sites

related to exercising.

B7. Self-education, Self-university.

B8. Analyzing Your Preferred Learning

Environment.

B9. Relaxation

Training.

B10. Memory

Enhancement Techniques.

Here is a related

site suggested by Jose, a middle school student: Memory

and the Human Brain.

B11. Learning with

Computers.

B12. Using

Self-Paced Modules.

B13. Using

Communication Technology.

B14.

Self-Directed Learning Modules.

B15. Learning from Your

Experiences.

B16. The Use of Penetrating

Questions.

B17. Designing

a Personal Learning Project.

B18. Walkabout.

B19. Developing

Lists of Resources.

B20. Using

Mediated Resources.

B21. Repertory

Grid-Based Technique.

B22.

Correspondence Study.

B23.

Constructing a Planning/Design Model.

B24. Improving Writing

Skills.

B25.

Individualized Learning within an Organizational Setting.

Increasingly, more

and more organizations are recognizing the value in providing resources and

opportunities for employees to "train" themselves through various

self-directed techniques.Guglielmino

and Guglielmino (1994) suggest

several resources that are being established in some organizations.

C. Personal

Reflection Tools

C1. Book/Article/Media Review

Techniques.

C2. Creating an Interactive Reading Log.

The interactive

reading log is a learning activity designed to give you a thoughtful exposure

to a broad area of subject matter. It is intended to place relatively greater

stress on reading and less stress on intensive writing related to a limited

topic. A log is not an outline nor a summary of your reading. Rather, it is

essentially a series of reactions to those elements in your readings that are

particularly meaningful and/or provocative.

C3. Creating a Media Log.

C4. Journal/Diary Writing Techniques.

The personalized

journal or diary is a tool to aid you in terms of personal growth, synthesis,

and/or reflection on any new knowledge that is acquired in learning efforts.

You are shown how a diary can be created and given examples of how others have

created one.

C5. Creating your Personal Philosophy

Statement.

The way one

teaches is tied to a personal philosophy of life. This activity helps you

understand more about various philosophical models or frameworks. You are shown

how to eclectically draw from various models in creating your own statement of philosophy. An

instrument developed by Lorraine M. Zinn, that demonstrates your preference for

various philosophical viewsis available or can be found in Zinn, L. M. (1990).

Identifying your philosophical orientation. In M. W. Galbraith (Ed.), Adult learning

methods: A guide for effective instruction (pp. 39-77). Malabar, FL: Krieger

Publishing Company

C6. Analyzing a

Theory.

C8. Reading a Book

Proactively.

C9. Using Human

Resources Proactively.

C10. Learning

Through Intuition and Dreams.

C11. Reflecting

on Learning at Home or the Workplace.

C12. Analyzing

Your Thinking Skills.

C13. Relaxation. Dealing with

stress.

C14. Imaginary

Dialogues.

C15. Analyzing Personal Ethics.

C16. Thinking

About Learning.

C17. Personal Inventories.

C18. Personality Measures.

D. Individual

Skill Development

D1. Skill

Practice Exercises.

D2. Portfolio

Development. Here is one good resource. Here is a second one.

D3. Improving

Your Writing Skills.

D4. Enhancing Your

Lecturing Skills.

D5. Enhancing

Your Discussing Skills.

D6. Enhancing

Your Questioning Skills.

D7. Enhancing

Your Coaching Skills.

D8. Enhancing

Your Understanding of Various Teaching Techniques.

D9. Effective

Use of Gaming Devices.

D10. Using a

Study Center/Learning Lab.

E. Group Study

Techniques

E2. Debates.

E3. Discussion

Groups or Discussion Networks.

E4. Quality Circles.

E5. Study Clubs/Study Circles.

F. Using The

Educative Community

F1. Community Study.

There are a

variety of resources existing in any community that can be used to meet various

of your education or training needs. You are shown how to better understand

this educative community notion by using various community study techniques.

You learn how to seek out that information important for your personal growth

and development.

F2. Using

Another Person as a Resource for Learning.

F3. Obtaining

Feedback from Others.

F4. Agency

Visit. Here is an interview schedule you could use to examine an agency and

determine its potential for self-directed learning. Here is a guide for analyzing the potential within an

agency for learner control.

F5. Mini-Internship.

F6. Interviewing Adult Learners.

It is assumed that

you can learn a great deal about your own learning from studying, observing,

and/or talking with other adult learners. You are shown how to interview adults

to determine what you can about their learning activities, approaches, and resource

preferences. You then are encouraged to derive a statement of personal

reflection and assessment in terms of your own learning needs and approaches.

F8. Obtaining

Feedback.

F9. Learning From Mentors. Thoughts on Mentoring.

F10. Learning

From a Resource.

F11. Career

Counseling.

F12. Organizational Audit.

F13. Power

Structure Analysis.

F14. Peer

Review.

F15. Peer Coaching.

F16. Using A Library

and the Web.

F17. Attending

a Conference.

F18. Using Museums/Art Galleries.

F19. Travel as

a Learning Event.

F20. Networks

and Networking.

F21. Study

Tours.

F22. Directed

Learning.

Figure 4. Techniques, Tools, and Resources for the

Self-Directed Learner

References

Ashman, A. F., & Conway, R. N. F. (1993). Cognitive strategies for special education.

New York: Routledge.

Ashman, A. F., & Elkins, J. (Eds.). (1990). Educating children with special needs.

New York: Prentice Hall.

Beziat, C. (1990). Educating America’s last minority:

Adult education’s role in the Americans with Disabilities Act. Adult Learning, 2(2), 21-23.

Biggs, J. B., & Moore, P. J. (1993). The process of learning. New York:

Prentice Hall.

Brockett, R. G. (1997). Humanism as an instructional

paradigm. In C. R. Dills & A. J. Romiszowski (Eds.), Instructional development paradigms. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Educational Technology Publications.

Brockett, R. G., & Hiemstra, R. (1991). Self-direction in adult learning:

Perspectives on theory, research, and practice. New York: Routledge.

Bureau of Census. (1994). Americans with disabilities (Statistical

Brief, January, 1994). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economic

and Statistics Administration.

Center for People With Disabilities. (1997).

Agency information. Boulder, CO:

Center for People With Disabilities. [On-line]. Available: http://bcn.boulder.co.us/human-social/cpwd/

Conti, G. J. (1979). Principles of

adult learning scale. Proceedings of the

Twentieth Annual Adult Education Research Conference. Ann Arbor, MI: Adult

Education Program, University of Michigan.

Coombs, N. (1989). Using distance

education technologies to overcome physical disabilities. In R. Mason & A.

Kaye (Eds.), Mindweave: Communication,

computers, and distance education. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Craik,

G. L. (1840). Pursuit of knowledge under

difficulties: Its pleasures and rewards New York: Harper & Brothers.

Gadbow, N. F., & DuBois, D. A.

(1998). Adult learners with special

needs: Strategies and resources for postsecondary education and workplace

training. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

Guglielmino, L. M. (1977). Development

of the self-directed learning readiness scale. (Doctoral dissertation,

University of Georgia, 1977). Dissertation

Abstracts International, 38, 6467A.

Hiemstra, R. (1988). Translating

personal values and philosophy into practical action. In R. G. Brockett (Ed.), Ethical issues in adult education. New

York: Teachers College Press.

Hiemstra,

R. (Ed.). (1991). Creating environments

for effective adult learning (New Directions for Adult and Continuing

Education, No. 50). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [On-line]. Available: http://roghiemstra.com/leindex.html

Hiemstra, R. (1997). Applying the individualizing

instruction model with adult learners. In C. R. Dills & A. J. Romiszowski

(Eds.), Instructional development

paradigms. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Hiemstra, R., & Brockett, R. G. (1994). From

behaviorism to humanism: Incorporating self-direction in learning concepts into

the instructional design process. In H. B. Long & Associates, New ideas about self-directed learning.

Norman, OK: Oklahoma Research Center for Continuing Professional and Higher

Education, University of Oklahoma.

Hiemstra,

R., & Sisco, B. (1990). Individualizing

instruction: Making learning personal, empowering, and successful. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [On-line]. Available: http://roghiemstra.com/iiindex.html

Houle,

C. O. (1961). The inquiring mind.

Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin, Press.

Jacobowitz,

T. (1990). AIM: A metacognitive strategy for constructing the main idea of

text. Journal of Reading, May,

620-624.

Knowles,

M. S. (1986). Using learning contracts:

Practical approaches to individualizing and structuring learning. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lokerson,

J. (1992). Learning disabilities:

Glossary of some important terms. (ERIC Digest #E517). Reston, VA: ERIC

Clearinghouse on Handicapped and Gifted Children, Council for Exceptional

Children. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 352 780)

Preece,

J. (1995). Disability and adult education – the consumer view. Disability and Society, 10(1), 87-102.

Rohfeld,

R., & Hiemstra, R. (1995). Moderating discussions in the electronic

classroom. In Z. L. Burge & M. P.

Collins (Eds.), Computer-mediated

communications and the online classroom. Volume III: Distance Learning. Cresskill,

NJ: Hampton Press Inc. [On-line]. Available: http://roghiemstra.com/moderating.html

Sisco, B. (1997). The individualizing instruction

model for adult learners. In C. R. Dills & A. J. Romiszowski (Eds.), Instructional development paradigms.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Smiles,

S. (1859). Self help. London, UK:

John Murray.

Smith,

R. M., & Associates. (1990). Learning

to learn across the life span. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tough,

A. (1979). The adult’s learning projects:

A fresh approach to theory and practice in adult learning (2nd

Edition). San Diego: CA: University Associates, Learning Concepts.

Wehmeyer,

M. L. (1992). Self-determination and the education of students with mental

retardation. Education and Training in

Mental Retardation, 27, 302-314.

Whitman,

T. (1990). Self-regulation and mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 94, 347-362.

Willis,

B. (Ed.). (1994). Distance education:

Strategies and tools. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology

Publications.