Page 1

ONE

The Nature Of The Community

What is a Community?

What is a community? This is an interesting question to ask but a difficult one to answer. Many scholars have attempted to define community or to describe what makes up a community and Galbraith (1990) talks about the multi-dimensionality of community. Massey (1992) also describes how changes in the world economy are impacting on visions of "home," "place," or "locality." In concert with the main theme of this book, Decker (1992) suggests that communities need to be where learning can take place. Various sources referenced at the end of this chapter provide these varied and contrasting conceptions or dimensions of community.

The word "community" comes from the Latin term, Communis, meaning fellowship or common relations and feelings. In its medieval usage the word was perhaps more descriptive, meaning a body of fellows or fellow townspeople. This definition is still relevant, since the average person today usually defines community in reference to locality, such as a hometown, place of residence, or neighborhood.

However, there are many other ways of examining the meaning of community beyond a locality reference. This does not mean that the community as a locality base is dying out; rather, the nature of community is complex and changing. Thus, more precision is needed to promote an understanding of community adequate enough for effective living and survival in a situation of change.

One of the least precise ways for describing a community is to place it at either of two opposite poles. Yet, such a description often is used. Such polarities have been variously described as the range from rural to urban, folk culture to mass culture, simple organization to complex, or Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft (see the definitions later in this chapter). In whatever way these contrasting positions are described, they provide little assistance in helping you describe a personal perception of community.

On a slightly higher scale of precision, community can be described strictly on the basis of geographic locality. This is perhaps the one community descriptor with which most people are familiar. Included would be such statements as: "Kalamazoo, Michigan, is my home community!" "I was born in New York." "I came from Vancouver, British Columbia." "I moved to a retirement village in southern Florida." "I'm a United States citizen." Thus, locality can range from individual perceptions of a neighborhood or small city to even a state, province, or country. The difficulty in

Page 2

utilizing locality as a common reference base is this variability in size and area of inclusion as perceived by different people. However, locality will be utilized often in this book when talking generally about communities.

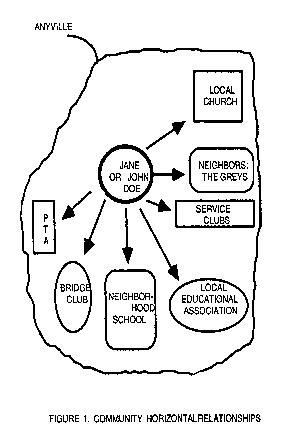

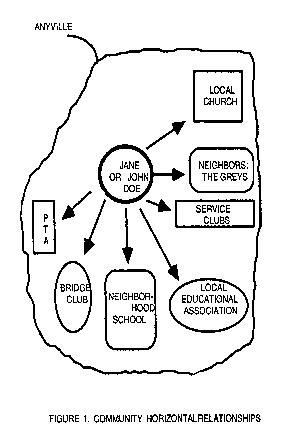

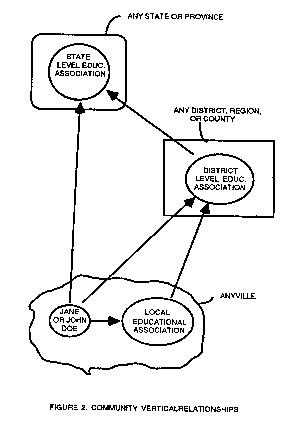

A third manner in which community can be described or defined, and one precise enough to allow for some common understanding, is through the horizontal and vertical axes of a locality. Although this framework developed by Warren (1978) is somewhat abstract, it allows for the shared interests and behavior patterns of people in one locality to be analyzed. The framework will be utilized to provide a basic definition for community. Figures 1 and 2 display the horizontal and vertical relationships.

The framework's horizontal axis emphasizes notions of the locality feature described above. Think of it as people-to-people associations throughout a neighborhood or community. It involves the relationship of one individual to another individual or one group to another group in the same locality. An illustration would be a group of citizens coming together to form a MADD (Mothers Against Drunken Drivers) or drug awareness group or the local United Way organization sponsoring and administering their annual fund campaign. The organizing and coordinating roles performed are primarily local, although there may be national, provincial, or state organizations that provide various types of support.

The framework's vertical axis emphasizes a feature of community activity not yet mentioned, that of an individual's or group's special interests. Here the concern is with an individual's relationship to, or membership affiliation with, a local interest group that usually is associated with a state, provincial, regional, or national group. The person-to-person or person-to-group association is rooted in a locality base but branches upward (out of the geographic community) into other and different locality bases. This can be illustrated by an adult educator or elementary school teacher's membership in a local educational association which is on the horizontal axis and the relationship of this association with county, state, provincial, regional, or national associations on a vertical axis.

The aim in either horizontal or vertical associations is to achieve some special goal, maintain some personal relationship, or resolve a particular problem.

The horizontal-vertical axes approach does not cover all aspects of "community" relationships. However, it does provide a basis for identifying and comparing a Jane Smith, teacher, Methodist, and liberal who lives on Woodward Avenue in Detroit to a George Bailey, banker, Catholic, and conservative who lives on some street in Chicago or Toronto.

To provide a common basis for comparison of people and groups, the following definition of community is offered: A community is "that combination of social units and systems which perform the major social functions having locality relevance" (Warren, 1978). In other words, the organization of social activities and units are designed in such a manner so as to facilitate the daily living of given sets of people. These people can have both horizontal and vertical relationships of varying types. A large neighborhood or suburb, a planned community, and a small community with surrounding rural areas might all fit within this

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

definition if the general needs of those residing there are met within the designated area.

It needs to be noted, though, that the dynamic state of modern society, due to rapid technological change and many other factors, is leading to a progressive reorganization of daily living. The vertical relationships described above are becoming increasingly more important. This shift from locality grouping toward interest grouping, or from horizontal grouping to vertical grouping, has been occurring for several years. Such shifting involves the entire structure of any community as a system of interdependent parts.

There are several diverse and contrasting definitions or conceptions of community which have not been discussed. You may be interested in pursuing further some of these different notions such as the physical community, social community, economic community, rural community, urban community, moral community, or human community. A community can be studied as space, people, shared activities, relationships among people, social processes, or political activity. Several sources covering these approaches are displayed in the bibliography at the conclusion of this chapter.

The Changing Community

Defining community also is complicated because of society's dynamic nature. Society's increasing complexity and the rapidity of change are realities most of us sense. Several authors have described how this complexity and change have brought about a shock or complexity in the way our future is viewed. Toffler (1970) more than two decades coined the term "future shock" to describe much of this change. More recently, Naisbitt (Naisbitt, 1984; Naisbitt & Aburdene, 1990) has described several of what he calls megatrends which are change and technology related. The "problem of the city," increasing bureaucracy and institutional complexity, social disorder and alienation, rising crime rates, increasing substance abuse, ever enlarging numbers of homeless, drive-by shootings, gang warfare, anti-abortion activism, gay bashing, high unemployment, concerns over AIDS, and various other frustrations are evidence that social change is affecting many phases of life.

Major changes that affect all communities and cause fragile and impersonal human ties are population growth, mobility, and urbanization. Even given a decline in the official U.S. birth rate during the past several years, legal and illegal immigration and estimated population growth suggests that in two decades, three at the most, another 100 million people may be residing in the United States. This represents approximately a 50 percent increase over current numbers. The growth rate in many countries is considerably higher and is creating a whole host of severe problems.

The population in many industrialized countries has been quite mobile--many people moving to or near larger cities. For example, nearly

Page 6

75 percent of the United States people now live on about 1 percent of the land, and this urbanization has taken place primarily in the past four to five decades. Consequently, most communities are experiencing a nightmarish task finding needed resources, providing services, and managing their ever more complex human relationships. This problem is even magnified in many small communities where an aging population is on the increase and the number of people supporting social endeavors through their employment, service, and taxes are often on the decline.

Another phenomenon related to population change and urbanization, and in many cases caused by these factors, is the technological revolution. All phases of society throughout the world have been affected by the resulting changes. For example, technology often has increased specialization which has led to more and larger organizations, greater bureaucracy, and growing impersonalness among workers. In the U.S., international ownership of businesses and the loss of jobs to other areas or even to other countries also has become a growing reality. Consequently, ties to a community for whatever reason are becoming slight or often only temporary and transitory.

A final complexity to be mentioned in relation to the changing community is the tremendous and rapid increase in organizations and groups. Today a person can belong to any number of local groups (the horizontal dimension). In addition, membership in state and national organizations is also quite common (the vertical dimension). The consolidated power of large organizations or groups is often central to getting things done, witness in the U.S. the rapid growth in power of PAC groups. However, this situation frequently tends to weaken individual ties to a locality and makes understanding the nature of community more difficult.

What might the nature of the changing communities become in the next several years? There is mounting evidence that communities will continue to change for some time. Some people suggest that new communities should be built in remote areas to accommodate expected future population growth. Some planners envision a quarter of a million people living in such communities in the future. A major problem is determining how to provide employment for such residents.

Some designers have been building special satellite communities or suburbs surrounding large cities but connected to them by rapid transit systems and super expressways. Three of the more famous U.S. communities of this nature now in existence are the following: Reston, Virginia; Columbia, Maryland; and Litchfield Park, Arizona. Their unique features include special street plans that limit the need for automobiles,

Page 7

neighborhood village centers within easy walking distance, and housing clustered around recreational centers. Some employment opportunities are provided within these communities, but many residents who earn regular salaries must commute to large cities for work.

Some people see systems of cities (each system called a megolopolis) becoming more and more tied together in huge population masses over a wide range of land. It is as though each city is an organism that continues to grow until it links with another to become one. Some futurists suggests that future United States megolopoli will stretch from San Diego to San Francisco, from Chicago to Detroit, and from Washington, D.C. to New York City. Many other such systems in the U.S. and other countries could develop in the next two or three decades although a lot of interest in conservation or environmental protection issues, return to rural living desires, and back to nature life styles may slow their emergence.

While Beale (1975) and other demographers are suggesting that migration back to rural areas is taking place in many parts of the United States, continuing evidence can be found that cities receive a steady stream of new citizens each year through people seeking employment and people moving from or fleeing other countries in addition to internal population growth. Thus, there are some who suggest that the United States's future lies only in the larger cities. The small community is thought doomed because of diminishing employment opportunities and the increasing costs of providing many basic services.

As cities continue to grow, what can be done to make them better places in which to live? The present population densities of portions of many cities are not really very high. Obviously, there is overcrowding in the low-income sections of many cities, but this can be corrected. Wasted land can be found in most cities in the form of hugh parking lots, public utility right of ways, and vacant eyesores. This land can be utilized in several ways and most authorities indicate that cities will find it much less expensive to expand inward rather than outward. Existing water, sewer, and public utility lines can be utilized and long-distance transportation schemes will not be so critically needed.

That is not to say that problems associated with crowded conditions and inadequate infrastructures won't accompany continual population growth in most cities. Certainly these problems must be solved. What is to prevent, for example, schools from being built over parks, 30 story apartment complexes from being constructed that are self-contained (including educational and employment opportunities), and shopping centers from being constructed over city reservoirs. Some cities now provide special incentives and even funding for restoration of businesses and homes in the inner cities. "Habitat for Humanity" and similar groups are building homes for low-income residents. Such activities can and will happen, but they require careful and coordinated planning.

Page 8

The person living in a rural or sparsely populated area might think that the foregoing discussion has no personal meaning. However, the United States, for example, like most countries in the world, finds its economy tied closely to wherever the country's population is concentrated. So all types of locality bases must be of concern and understood if the problems within each which often affect the national economy and well-being are to be solved. Further, the discussion above was intended to illustrate that the modern community is a changing one. All possible developments must be considered to understand how to live successfully with change.

Why Should You Know Your Community?

Knowing your community, the different ways in which people might think about what is called community, and how it is changing are important aspects of effective living. Whether a person is a teacher, student, or lifetime resident of some community, they are usually interested in a better life for self and others. Consequently, the remaining chapters present and develop some concepts related to understanding how educational systems and communities fit together and how individuals and families can have a more effective role in this interdependent relationship.

There are many examples of U.S. citizens trying to have a role in local decision-making. The burning of school buses in Pontiac, Michigan, several years ago to prevent the cross-town bussing of children is one rather violent example. Boston had violent conflicts over the same issue, as did San Francisco's Chinatown residents who elected to keep their school-age children at home for several weeks as a protest. All three communities had staunch opponents of such change who claimed that bussing destroyed the rights of their children for an education which would include a locality-specific emphasis. Amish parents and members of what has been dubbed politically as the religious right are trying to win the permanent right for a religious emphasis to the education that their children receive. A peace group several years ago camped outside a New York military installation in an attempt to alter both local and national decision-making. During the hectic months before the 1992 Persian Gulf's "Desert Storm" military actions, many peace activists had bitter conflicts with more conservative groups. A better knowledge of how to work more effectively in the community might have prevented some of the sorrow and hard feelings that accompanied such situations.

A variety of problems are common to or affect almost every community. Yet, although communities share many similarities, they also share many dissimilarities. Thus, it becomes important to understand how to work and live effectively within any type of a community setting, especially in this mobile society where people frequently move from one area to another. Factors such as mobility and rapid change mean that each community can no longer be treated as though it were not associated with the rest of society. Any similarities that exist must be capitalized on; dissimilarities must be understood by change agents, community leaders, and others studying communities. The definition

Page 9

offered earlier and information in subsequent chapters will provide some of the basics for understanding and dealing with various community problems, especially an understanding of the sense of community and how to utilize community information that is obtained or available.

A sense of community, whether it be horizontal, vertical, or both, is needed before any effective educational program can be implemented. A disorganized community is usually open to problems or exploitation by various forces. An illustration is the community that found itself paying triple the original estimate on the construction of a new airport parking garage because of strikes, materials delay, abnormally low bids, and contract irregularities. An organized community effort could have forced some type of settlement and salvaged some scarce dollars for more pressing needs.

All individuals are the products of their community. Individual channels of communication are through the community setting. Whatever the aim of any program, access to almost every individual who will be affected is through some community channel, program, or leader. This does not imply that the manipulation of people is included in this access route. Each community citizen must be respected as a person. Furthermore, any community effort should involve people who relate to each other in a broad and deeply human way.

Finally, every community has some type of locality base, for there cannot be common living without some pattern of association that is horizontal in nature. In addition, there is also association that is vertical in nature or outward reaching beyond the local setting. These patterns of association are further complicated because most communities are changing constantly. Consequently, a person must learn how to live and work effectively at both horizontal and vertical levels. The remaining chapters will be devoted to developing some concepts and ideas essential to this learning endeavor.

Some Definitions

Community -- The organization of various social activities and units in such a manner that the daily living of a certain set of people is facilitated.

Gemeinschaft -- Shared, intimate, and personal relationships built around the interdependence of primary social groups in a locality setting.

Page 10

Gesellschaft -- Impersonal, logical, and formally contracted associations between people who are independent from each other. Bureaucracy is a product of gesellschaft.

Horizontal Relationship -- The association of one individual to another individual within the same locality such as a neighborhood or a city.

Locality Setting -- A specific or recognizable geographic setting in which a group of people reside.

PAC -- A political action committee in the United States that provides a lobbying force built around a special or particular interest. The lobbying can take place at local, state, or national levels.

Vertical Relationship -- The association of an individual to another individual or to a group based primarily on membership affiliation. This affiliation often includes membership outside the locality setting.

Study Stimulators

1. Each person has several horizontal and vertical pulls. List several that affect you. How have some of the pulls affected you as a citizen in terms of loyalty, time constraints, and citizen involvement?

2. Develop a definition of community that fits your personal situation. Who is included within that definition? Who is excluded? Is inclusiveness a difficult issue for most people?

3. Complete a study of some community with which you are familiar. Look at the adequacy of the educational resources in light of perceived needs. Does a "feeling" or "sense" of community exist?

4. Interview one or more community agency officials. What are their opinions and feelings regarding "community" and education?

5. What does the future likely hold in store for "your" community?

6. Has your community experienced any in-migration or out-migration of people? What have been the resulting implications?

Selected Bibliography

Abrahamson, J. (1959). A neighborhood finds itself. New York: Harper & Brothers. 334 pages. Appendices. Bibliography. Index. The author, an employee of the community agency involved, describes the story of an innovative effort in a declining Chicago area to "fuse the challenges of . . . (Black) in-migration and conservation into the excitement faced with similar problems." Especially valuable is her very frank review of the various mistakes made by the quite successful Hyde Park-Kenwood community endeavor.

Page 11

Baltzell, E. D. (Ed.). (1968). The search for community. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. 162 pages. Selective Bibliography. In this book there are nine chapters aimed at promoting an understanding of the "various" communities that exist in the United States.

Beale, C. L. (1975). The revival of population growth in nonmetropolitan America (ERS-605). Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 16 pages. A report displaying information on the rate of population growth in non-metropolitan areas which out stripped the growth in metropolitan counties.

Bell, C., & Newby, H. (1972). Community studies. New York: Praeger Publishers. 262 pages. Author index. Subject Index. Such topics as community theories, community study techniques, and community power are discussed. In addition, several American and European case studies are presented.

Biddle, W. W., & Biddle, L. J. (1965). The community development process: The rediscovery of local initiative. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc. 334 pages. Appendices. Bibliography. Index. The authors are guided by the philosophy that community development is essentially human development. They identify the means by which citizens in the small towns and urban neighborhoods of American can be encouraged to take action in an attempt to improve their local situation and to create or reaffirm a sense of community.

Decker, L. E. (1992). Building learning communities: The realities of educational restructuring. Community Education Journal, 19(3), 5-7. The author in this article describes how a community's educational institutions must be interconnected with its growth and development. He suggests a process for building learning communities.

Effrat, M. P. (Ed.). (1974). The community. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. 323 pages. Twelve chapters make up the book. Topics covered include such topics as community disorganization, political change, utopia communities, and community planning.

French, R. M. (Ed.). (1969). The community: A comparative perspective. Itasca, IL: F. E. Peacock Publishers, Inc. 519 pages. This mammoth volume includes contributions in 44 chapters from numerous authors. Topics covered include community theory, community organizations, changing communities, and the fate of the local community.

Galbraith, M. W. (Ed.). (1990). Education through community organizations (New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, No. 47). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 98 pages. Index. References. This book offers an in-depth examination of the unique role played by community-based organizations in providing adults with lifelong educational opportunities. The book has 11 chapters with Chapters 1 and 11 useful for examining the nature of community.

Long, H. B., Anderson, R. L., & Blubaugh, J. A. (1975). Approaches to community development. Iowa City, IA: National University Extension Association and American College Testing Program. 86 pages. Seven chapters make up this monograph, with six approaches to promoting community development covered.

Page 12

MacIver, R. M. (1970). On community, society, and power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 319 pages. Index. Bibliography. The book covers such topics as the primacy of community, social processes, democracy, and the nature of social science.

Massey, D. (1992). A place called home? New Formations, 17(Summer), 3-15. In this article the author explores how various changes are affecting the way people view community as a concept. Worldwide economies and communication improvements are impacting rapidly on such views.

Naisbitt, J. (1984). Megatrends. New York: Warner books. 333 pages. Index. The author describes 10 of what he calls megatrends, or major movements throughout the world, but especially as they impact on the U.S. Several trends have direct implications for adult and community educators.

Naisbitt, J., & Aburdene, P. (1990). Megatrends 2000: Ten new directions for the 1990's. New York: Morrow. 384 pages. Index. A continuation of Naisbitt's effort to keep up-to-date with various social indicators. Several of the newly described trends have implications for adult and community education.

Sanders, I. T. (1953). Making good communities better. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press. 199 pages. Topical index. This book can be treated as a handbook on the community with a series of short articles telling readers what they can do to improve their communities. Some sections covered include "What Makes a Good Community," "How Communities Show Differences," and "Procedures for Civic Leaders.

Sanders, I. T. (1975). The community (3rd Edition). New York: Wiley & sons. 526 pages. Author Index. Subject Index. This book provides considerable information on life in the modern American community. Such topics as the community, changes underway, and future changes expected are discussed.

Sutter, R. E. (1973). The next place you come to. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. 214 pages. Index. This book is an historical introduction to North American communities. It provides a useful background for reading about and understanding contemporary communities.

Suttles, G. D. (1972). The social construction of communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 278 pages. Index. The book has nine chapters on various aspects of understanding community. Such topics as the natural community, the contrived community, and territoriality are covered.

Swanson, B. E., & Swanson, E. (1977). Discovering the community. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 391 pages. Index. The book is divided into five major parts. Although something can be gleaned from all five, the first part on social dimensions of community may be the most useful. A discussion is provided on various community theories, in and out migration, and social stratification issues.

Toffler, A. (1970). Future shock. New York: Random House. 505 pages. Bibliography. Index. This book is about what is happening to people who are overwhelmed by change. The author explores how change affects the communities in which people live, the organizations to which they belong, and their associations with one another. Some suggestions for coping with the rapidity of change are offered.

Page 13

Warren, R. L. (1978). The community in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 44 pages. Author Index. It is the thesis of the book that changes in community living include an increasing orientation of local organizations and individuals toward extra-community systems. This phenomenon has resulted in a corresponding decline of community cohesion and autonomy. Suggested are some community action models for dealing with the changes. Locality relevance and horizontal/vertical patterns are analyzed.

________________________________

-- Return to Roger Hiemstra's opening page

-- Return to Roger Hiemstra's opening page

-- Return to The Educative Community Contents page

-- Return to The Educative Community Contents page

-- Go to

Information about the

author,

-- Go to

Information about the

author,  -- Go to

the Preface,

Chapter Two,

Chapter Three,

Chapter Four,

Chapter Five,

Chapter Six,

Chapter Seven,

Chapter Eight, or

the Index

-- Go to

the Preface,

Chapter Two,

Chapter Three,

Chapter Four,

Chapter Five,

Chapter Six,

Chapter Seven,

Chapter Eight, or

the Index