MAY NO ONE BE A STRANGER

150 YEARS OF UNITARIAN PRESENCE IN

by

Jean M. Hoefer

and

Irene Baros-Johnson

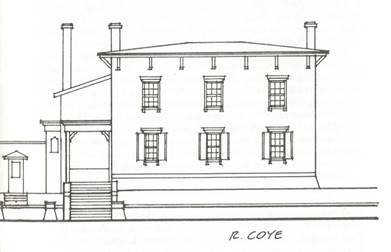

Drawings by Robert Coye

Logo Design by Dorothy Ashley

[Reprinted here by

permission]

MAY MEMORIAL UNITARIAN SOCIETY

1838 – 1988

[Web Page Additions by Roger Hiemstra, MMUUS

Archivist]

[Note: See

the Invitation At the End of This Document to

Help Write

the 1988-2006 History]

[page ii]

Copyright @ 1988

May Memorial Unitarian Society

Typeset and Printed by

The Printers Devil North, Inc.

[page

iii]

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Foreward

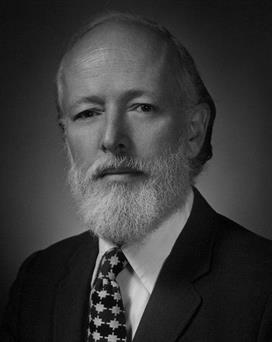

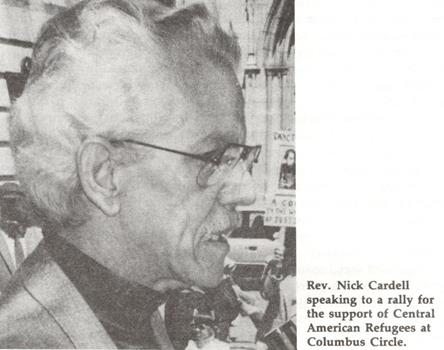

– Rev. Dr. Nicholas C. Cardell, Jr. 1

A

New Field in the West 1838-1844 3

Rev. John P. B. Storer

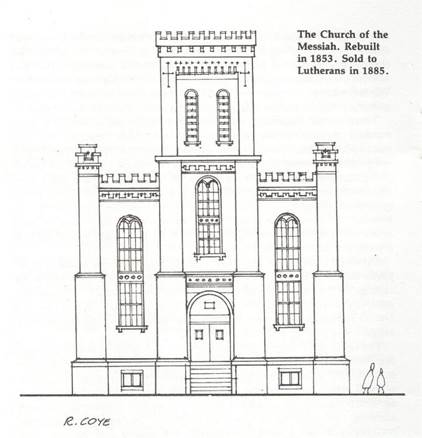

The Church of the Messiah

To

Exercise a Larger Liberty 1845-1874 7

Rev. Samuel J. May

Abolition

Woman Suffrage

Education Reforms

Onward

and Upward 1868-1917 18

Rev. Samuel R. Calthrop

May

Rev. John H. Applebee

100 Years and Beyond 1917-1952 26

Rev. Applebee

Rev. W. W. W. Argow

Centennial Celebration

Parish House

Rev. Robert E. Romig

Rev. Glenn O. Canfield

Growth, Form, Movement 1952-1964 35

Rev. Robert L. Zoerheide

Relocation

Rev. John C. Fuller

May

Memorial Unitarian Society 1964-1973 44

New building on

Social Change and Hard Times

Open Channels 1973-1988 51

Rev. Nicholas C Cardell, Jr.

Sanctuary

Conclusion 59

Biographical Briefs 60

Index 62

[page

iv]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The

official minutes of our Unitarian society's board of trustees and

congregational meetings are the primary source of this history, along with the

documents in our archive files. We used material from Elizabeth Walsh's and Helen

Saddington's centennial book A Backward Glance O'er

Traveled Roads. The scrapbooks kept by the society's historians over

the years and the memories of our members furnished many interesting details.

We also found information in the files at the Onondaga Historical Association,

the archives of the Unitarian Universalist Association in Boston, and the

library of the Meadville/Lombard Theological School in Chicago. We are indebted

to the staffs of the OHA and of Meadville Library and to UUA archivist Rev.

Mark Harris for their help, and to Dr. Sally Roesch

Wagner who furnished the quotation from Matilda Joslyn Gage. We also owe a

large debt of gratitude to the many people in the congregation who helped us

gather information and who read and critiqued the manuscript.

[page

1]

FOREWORD

Histories

of congregations are usually organized around the ministers who served them,

and focused on the styles and emphases of their ministries. This history is no

exception. It is probably the most practical approach, but it does not do

justice to the multitude of individuals who were and are the congregation.

One

of my colleagues, the Reverend Jack Mendelsohn, observed many years ago that

"Great churches make great ministers." Looking back over the roster

of ministers who served this society, it is clear that May Memorial has always

been a "great" congregation. The ministry of any religious community

depends for its fruitfulness not only on support for ministry, but also on

participation in it.

For

thoughtful, conscious life, all creation is precariously contained in a mended

cup of meaning. It is the cup from which we drink our lives, the cup with which

we drink to life. It is a cup that is broken and mended, broken and mended,

over and over again. Each time an era passes, a way of life is destroyed, or

someone of significance to us dies, we may cry out that our cup is broken. It

is at such times that we need each other and are needed.

Celebration

and healing are our tasks. Celebrating the wonders and mysteries of life, and

healing – the mending of broken cups and broken lives – these are the ministry

to which all of us are called. Nurturing and comforting each other in May

Memorial, and reaching out in compassion to those in our larger community whose

cups and lives have been broken by the mystery of fate or the cruelty of

injustice, these are the tasks that mark many of the high points in the history

of this congregation's ministry. It is a ministry that will always need a

"great" congregation.

NICK CARDELL, JR.

[page 2]

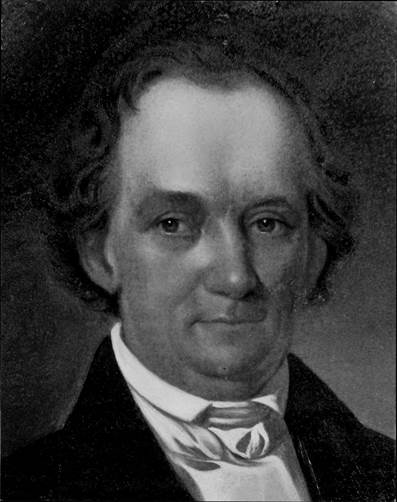

Rev. John P.

B. Storer, first minister 1838-1844

[page 3]

A NEW FIELD IN THE WEST

A

Unitarian society started in Syracuse during the 1830s, only a few years after

the Erie Canal had opened across New York State. In one generation Syracuse had

grown from a muddy four corners to a village of more than 3,000 people,

comfortable homes, busy offices, and warehouses. There were also taverns and

other nightspots where "canawlers" could

roister away the tedium of long days and nights on the silent waterway. In

several churches the pious listened nightly to tirades about the fires of hell

delivered by resident ministers and traveling evangelists who battled Satan

along the frontier.

Shocked

and dismayed by the excesses of the fire and brimstone preachers, Christians as

well as free thinkers came out to listen when Unitarian heretics came through

from New England to speak about a free religion of reason and brotherhood.

Syracuse historian W. Freeman Galpin wrote that Unitarian Rev. Henry Ware spoke

in Syracuse. "For one runner employed by the Unitarians to give notice of

the gathering," Ware reported, "ten were put in pay by the orthodox

to tell people not to go." These efforts resulted in an audience of more

than 100 people when he spoke the next day.

In

the intervals between missionary visits, Unitarians and Universalists gathered

for informal religious discussions in their homes. With the help of visiting

ministers they wrote a covenant that was signed by 14 people in the parlor of

Lydia and Elisha F. Wallace on 13 September 1838 forming the Unitarian

Congregational Society of Syracuse. On 4 October 1838 Dr. Hiram Hoyt and

Stephen Abbott presided at a meeting in Dr. Mayo's schoolhouse on Church (now

Willow) Street where Elihu Walter, Joel Owen, and Stephen Abbott were elected

the first trustees. The new congregation began a subscription to collect funds

for a church building and invited the Unitarians in Boston to help them find a

minister. A wooden chapel that cost $607 was completed at 317 East Genesee

Street in January 1839.

Several

visiting ministers came for a few weeks at a time to hold services and minister

to the people. One of the new church officers wrote the General Secretary in

[page

4]

but

so rapidly increased, that he soon had the satisfaction of addressing a

numerous and respectable audience. The Unitarian society at Syracuse by a

unanimous vote invited Mr. Storer to become their Pastor." On 30 March

1839 John Storer wrote to his congregation in Walpole that he was very happy

there and felt strongly attached to them, but he had made the painful decision

that "...it is my duty to go to the West...to tend a new field in the

Vineyard of the Lord."

John Storer moved to Syracuse in

the spring of 1839 to minister to the congregation of the "little

tabernacle," as he called the new chapel. His installation service on 20

June was held in the Methodist Church, because the little tabernacle was too

small to hold all the congregation and out-of-town visitors who attended. A

bachelor, Storer lived at the Syracuse House, a thriving hotel not far from the

canal docks, where distinguished travelers stayed and many important meetings were

held. Storer was described by those who knew him as a noble Christian, both

charming and scholarly. He had an intuitive sympathy for the joys -and sorrows

of all people from childhood through old age. Under his leadership the church

prospered and grew in spite of orthodox intolerance. A group of young men dared

to brave the storm and sneers of Orthodoxy by joining the society, although

social ostracism was so strong that few young women could face it. In 1877 C.

F. Williston, once mayor of Syracuse, reminisced in a letter to Rev. Samuel

Calthrop, "The notorious Elder Knapp used the Baptist Pulpit almost

nightly for weeks denouncing the Unitarian Devils as he called us, at the same

time asked pardon of 'Old Satan' for slandering him in that manner."

The

Unitarian congregation soon outgrew the little chapel described in Christian

Register as "a small and lowly tenement, which looked more like a

wood- house than a place of worship." After the Unitarians moved out, the

small wooden chapel continued to shelter new congregations, including the

Second Presbyterian, the Second Baptists, the Reformed Dutch, and the Wesleyan

Methodists.

Our

archives contain two letters written by members of the society in March 1840 to

John Townsend, one of the largest landowners and developers in the village.

They wrote to apply to the land company for a lot on which to build a Unitarian

church, because the Baptist, Presbyterian, and Episcopal "houses"

were all built on lots donated by Townsend's company. There is no further record

of the application, but it must have been turned down, because in August 1840

the society appointed Hiram Putnam, John Wilkinson, William Malcolm, Parley

Bassett, and Thomas Spencer to a committee to select and buy a lot for a larger

building. The women of the society financed the purchase with "avails from

fairs" and two lots on

[page

5]

The

corner

of Burnet, were bought for $1,000. In the

In

the summer of 1842 Mr. Storer traveled through

Between

the signing of contracts on

[page

6]

denominations.

The cornerstone was laid 27 June, the building completed that fall, and

dedication of the Church of the Messiah was celebrated on

Shortly

after moving to

The

Unitarian

ministers and friends from Storer's former congregations traveled to

[page 7]

TO EXERCISE A LARGER

Rev.

Samuel Joseph May preached his first sermon in

Samuel

Joseph May was born in

When

Sam May came back to Syracuse as a candidate for the pulpit opened by the death

of John Storer, he made sure that the congregation understood his commitments

to peace, temperance, and especially abolition. He had left two previous

ministries after conflicts with parishioners who objected to holding abolition

meetings and who wanted Negroes to sit in separate pews. During the past two

years in his position as head of a teacher's training school he had been

criticized for being a model of radical activism among his students. He wrote

about his candidating in

[page

8]

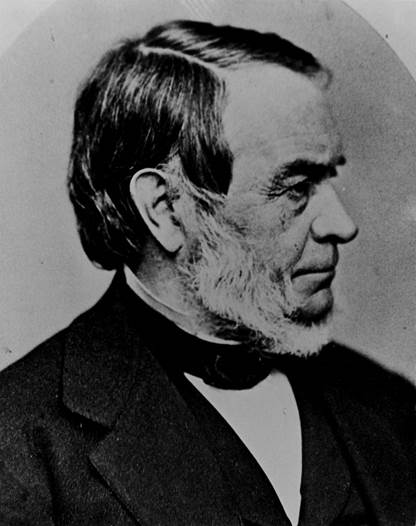

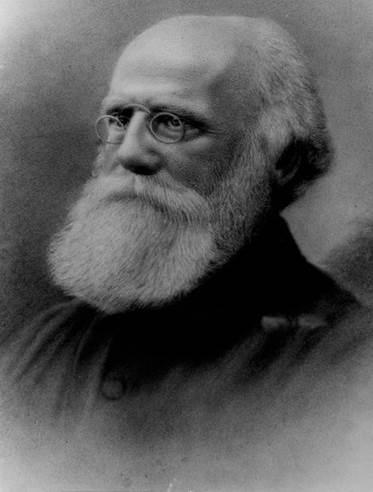

Rev. Samuel

J. May, second minister 1845-1868

After accepting the congregation's

unanimous invitation to be minister of the Church of the Messiah in late

1844, Sam May lingered in Massachusetts to help resolve a property dispute

between two factions of a divided church in Lexington, and to give Lucretia

time to recover from a premature delivery. The May family moved to

The

raw canal town troubled the

[page

9]

worked

together for state legislation to provide education and housing for canal boys.

The boys were rowdy, ignorant canal workers, usually homeless or runaway youths

who were shamefully exploited and often in trouble with the law. May also

helped start a school for children at the Onondaga Indian Reservation. A

planning group met at the Congregational Church in February 1846 and by

November of the same year a school building with seats and desks for 70 pupils

was dedicated at the Reservation. May and others acted within the cultural bias

of their time by setting a curriculum that taught farming and housekeeping

skills and emphasized steady work habits. More than a century passed before

educators considered including the language and traditions of the Onondaga

Nation in the school curriculum.

With

some of his church members and other philanthropic friends, May started the

first hospital in

Sam

May's lifelong concern was to prevent unnecessary misery. Like his father, a

May

held community discussion meetings at City Hall. One of his parishioners,

Harriet Smith Mills (mother of suffragist Harriet May Mills), described the

openness of these Sunday afternoon meetings that were attended by ministers and

people from all different churches. She wrote, "...it seemed to me the

ideal way of seeking truth...as no one has the whole truth, and from none is it

fully hidden." She sensed a real communion at the meetings, a fellowship

and fraternity beyond the sectarian bonds that divide people.

May

had a less formal style than many ministers. He wore a suit, not a robe in the

pulpit. He invited to the communion table all who wished to commemorate the

life and teachings of Jesus as a divinely inspired model. The Christianity that

May preached and professed stressed freedom of thought. When he addressed the

[page

10]

free

will, but also for developing citizens capable of self-government. For Sam May,

the core of Unitarian theology lay in the human mind and heart, "...it can

do a man no good to assert to that as a truth, which he does not perceive to be

true; it can do his heart no good to obey a precept, which he does not from his

heart believe to be right." May advised the graduates to be open to

learning even from the poor and illiterate, who, he assured them, would put to

shame their privileged education.

Pacifism

and nonviolence were natural outgrowths of May's religion. He preached against

capital punishment, and the whole

May's

activism undoubtedly alienated some of his flock, but his loving attitude

toward all people regardless of their opinions made his church popular. His

congregation soon outgrew its building. In the autumn of 1850 they rebuilt one

end of the church to make it 20 feet longer, allowing the addition of 28 more

pews. They also added a spire on top of the bell tower, which was the cause of

a remarkable catastrophe little more than one year later. Early Sunday morning

29 February 1852 the church was destroyed "by a hurricane which struck the

spire; threw it directly upon the ridge pole, crushed down the whole roof,

burst out the side and end walls, and in one movement demolished the entire

building excepting the front and the foundation." When the Unitarians

arrived for Sunday services they found their church was a pile of rubble. Near

the

[page

11]

east

end of the building the roof of the Northrup family home was crushed by the

falling bricks, trapping two women in the ruins. The church had collapsed about

The

stunned Unitarians gathering around the fallen building were mocked by some

more orthodox observers who "exulted over the penalty" that the

Almighty had exacted from the "unbelievers." The congregation

arranged to hold emergency services in City Hall, and after pledging to

reimburse the owner of the damaged house, Sam May reassured his congregation

with "a very feeling sermon" based on the gospel according to Luke,

xiii, 4, 5: "Or those eighteen, upon whom the tower in Siloam fell, and

slew them, think ye that they were sinners above all men that dwelt in

Jerusalem? I tell you, Nay: but, except ye repent, ye shall all likewise

perish."

For

weeks the town was "rife with opinions on the matter of the punishment..."

But Mr. Northrup, a Methodist, took a moderate view saying, "If the storm

was God's punishment for unbelief, why was the steeple allowed to fall on our

house? We are orthodox. Don't make out God to be meaner than man. If your house

falls down, don't change your religion but change your carpenter."

The

Unitarian church trustees requested permission to hold services in the First

Presbyterian Church each Sabbath at

Once

again, H. N. White was designated by the trustees to oversee construction of

the church building. Most of the $10,000 cost of rebuilding came from a public

auction of pews, although $2,000 was contributed by friends in

The building was

rededicated on 14 April 1853. One local newspaper reported that the service

emphasized God's work: "Remember those in

[page

12]

bonds...those

in adversity...(and) to prevent men from putting the bottle in their neighbor's

mouth making him drunken also." Another paper printed Mr. May's entire dedication

sermon that "summoned ourselves and others to exercise a larger

liberty...to make religious doctrine and religious duty the subjects of their

own personal investigation."

The

anti- Unitarian sentiment in

[page

13]

cooperated

on abolition and temperance work. May accepted, and treated the citizens of

May

was a founding member of the American Antislavery Society. He frequently

arranged for the group to meet in

In

October 1851 May played a

leading role in the famous Jerry Rescue in which a large number of men,

including some leading citizens, stormed the jail and freed a former slave

named Jerry who had been arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act. An escape

attempt earlier in the day had failed and Jerry had been injured. May visited

him in jail and promised him that he would be freed. The successful rescue was

planned in the office of Dr. Hiram Hoyt, one of the founders of the Unitarian

society. The rescuers organized their operation carefully so that no one was

killed or seriously injured in the struggle, although the jail building

suffered a lot of damage. Other Syracusans considered the rescue an outrage

against law and order. They held a protest meeting and 677 citizens signed a

petition denouncing the "Jerry Riot" But there were strong

antislavery sympathizers like former Mayor Alfred H. Hovey who had chaired a

meeting of protest against the Fugitive Slave Act when it was passed in 1850.

Several of the principal rescuers (rioters) were arrested and Unitarians George

Barnes, Oliver T. Burt, Dr. Lyman Clary, and Captain Hiram Putnam put up most

of their bail, while Charles B. Sedgwick provided legal counsel. None of the

antislavery people who

[page

14]

participated

in Jerry's rescue were sent to jail. For years afterward, whenever Sam May

faced a controversy, he would remark with a twinkle that he was getting ready

for another Jerry Rescue.

Illness

kept May out of the fray during part of 1858 and most of 1859. He rested in

At

an antislavery convention in

Sam

May viewed the destruction and bloodshed of the Civil War as a judgment on both

the North and the South for participating in the sin of slavery. Young men from

his church enlisted in the army and many other members of the society

volunteered to aid the war effort. The women sewed, knitted, and prepared

bandages, the men worked with the Sanitary Commission to organize shipments of

supplies for the wounded. May traveled to

When

he spoke of the rights of citizens, May also included the rights of women.

Before he met antislavery activists Lucretia Mott and the Grimke sisters in the

early 1830s May had never questioned the common assumption that women were not

to engage in public affairs. Troubled at first by women speaking in public

places, he had listened with an open mind and soon adopted their cause as his

own. He invited women such as the Quaker leader Lucretia Mott and

Congregationalist Rev. Antoinette Brown to speak from his pulpit in

Some

Syracusans were shocked and outraged when May stood on the platform with women

who were wearing the controversial bloomer

[page

15]

costume.

He was reluctant to discuss women's clothing but was eventually persuaded to come

out against tight corsets and other disabling fashions when the conservative

clergy and press ridiculed the reformers. Soon afterward a group of village

ladies called on him to complain about this public discussion of women's dress,

announcing that they had a message for him from the Lord. May received them

cordially and remarked he did not doubt they had a message, but he did doubt

its authorship.

After

the Civil War, Sam May helped organize the Onondaga County Suffrage Association

and held a series of meetings at City Hall. He invited Elizabeth Cady Stanton

and Lucy Stone to speak, promising "two or three able, gentlemanly

opponents who are sincere in thinking our doctrines erroneous – and who will

give them an opportunity fully to vindicate those doctrines in every

particular." When the first National Conference of Unitarian Churches was

held in 1865, May stirred controversy by suggesting that Universalists should

also be invited, and that churches should send both men and women as delegates.

At the second national conference in 1866 two women from

Early

in his ministry May had seen the devastating effects of alcohol abuse on

individuals and their families, which led him to enlist in the temperance

movement. He taught temperance songs in his Sunday schools, urged the school

children to "sign the pledge" promising never to use alcohol, and

supported community temperance rallies wherever he lived. During his

All of May's deepest

convictions seemed to coalesce in his educational work, and this may have

been his most important and lasting contribution to Syracuse. In 1848 he worded

the resolutions at a public meeting that established the school system of the

newly incorporated City of

[page

16]

Council

was not interested, so May led a campaign to raise part of the money and

persuade the city to build the school. He recruited Andrew D. White, a

prominent educator who later became first president of Cornell, to collect

funds. He enlisted public enthusiasm at a meeting in the fall of 1866 and in

December the citizens voted $75,000 for the new high school, which was built at

After

May's term on the Board was over, a new elementary school on

In

1868 May resigned his pulpit because of ill health and the society called Rev.

Samuel Calthrop to be their minister. Lucretia May had died in 1865 and Sam

went to live at the home of his daughter, Charlotte May Wilkinson. He continued

to work as a missionary, preaching in nearby towns and villages and traveling

as far as

In

the summer of 1871 his friend Andrew White, president of

During

the night following White's. visit Sam May died, ending 26 years of loving

service to a community that had known him as pastor,

[page

17]

teacher,

and friend. They all came

to his funeral, people from rich homes and humble ones, from his own

religious society and many others, colleagues in his struggle for human and civil

rights, individuals he had helped and befriended. Black people in

In memory of Samuel Joseph May, born in Boston

September 12, 1797, died

in

The

tablet was installed below a large

stained glass window when the James Street church was dedicated in 1885 and

was not removed until the building was sold in 1963. At this writing its location is

unknown (Editor’s note: It was later located as this prior link shows).

Matilda Joslyn Gage, a radical feminist of the day, wrote after May's death,

"A curious ignoring of his position on (women's rights) took place at the

time of his funeral services, not one eulogist at church or grave even remotely

alluding to his full and well-known sympathy with the woman suffrage movement;

nor was a woman asked to speak upon that occasion."

The

Unitarian Society purchased a marble bust of May made by a young artist from

[page

18]

ONWARD AND UPWARD

A

man of great presence and enthusiasm, with a superb education and eight years

pastoral experience, a vigorous 39-year-old Samuel Calthrop accepted the call

of the Church of the Messiah to fill the pulpit so long occupied by Samuel

May. No one could ever take May's place, but the people had great hopes for

this big, handsome Englishman who had left the Church of England because it

worshipped “a bad god." He

had been an honor student preparing for the ministry at Cambridge University,

but was refused his diploma when he declined to subscribe to the articles

of faith of the English Church. He came to the

To

prepare himself for the American ministry, Calthrop lectured at Harvard and

then started a school for boys at

Financially

embarrassed by his move to

In

the spring of 1871 Calthrop moved his family from a house on

Changes

in the church followed Samuel Calthrop's arrival. The

board of trustees was enlarged from six to nine men, and the names of women

[page

19]

began

to appear in the official minutes, which always before had been exclusively

masculine. A committee was appointed to welcome and seat newcomers at Sunday

services. Pews were free and revenues to support the church came from an

"envelope system” of voluntary pledges. The church was mortgaged to pay

for renovations, including finishing the basement rooms for meetings and Sunday

school classes. Members argued hotly over allowing the “children" to dance

at church socials in the new basement. Among the many volunteer Sunday school

superintendents who served over the years, Mary Redfield Bagg

stands out for the graded course of study that she introduced at May Memorial.

It was adopted by other churches in the denomination for their Sunday schools.

During

the 1870s the congregation could not meet expenses and Mr. Calthrop took

several cuts in salary. In the face of continuing deficits, the church decided

to reinstate the sale of pews in 1878, and gave up the "envelope system"

of subscriptions completely several years later. The ladies of the congregation

received a special resolution of thanks in 1878 "for the very efficient

manner in which they had extinguished the church debt." As a group, the

church women were now pledging several hundred dollars a year in fund-raising

events. At this time they were not formally organized, but several years later

the women of May Memorial formed the Women's Auxiliary to the Unitarian

Association. This organization eventually became the Women's

The

new church meeting rooms were used by groups outside the congregation. For

several years Calthrop held classes there, inviting the public to study

subjects like astronomy, botany, geology, chemistry, Roman history, and the

Hebrew prophets. The Syracuse Botany Club was formed by his students and is

still active today. It was organized by members of a fern class taught by Lily

Barnes. Mrs. L. L. Goodrich was president for 30 years.

Calthrop

read omnivorously and kept his congregation informed about intellectual trends

and controversies. From his pulpit he dared to advocate that latest scientific

heresy, evolution. In 1871 he mentioned the subject in the graduation address

he gave at

[page

20]

University

awarded him an honorary LH.D. with the tribute, "There is no honorable

designation too good for him."

Sam

Calthrop's absent-mindedness was legendary. There are

several stories of his riding or driving his horses on some errand and then

walking home without them. It was said that, left to care for his baby

daughter, he deposited her with a neighbor, and when Mrs. Calthrop came home he

did not know where the child was. Once when Mrs. Calthrop was out for the

evening, he put the children to bed, and reported to her later that one of them

had put up quite a struggle. When she looked in on the sleeping children, she

found that the recalcitrant one was not hers but the child of a neighbor. One

summer he came to town from his summer camp at the head of

After

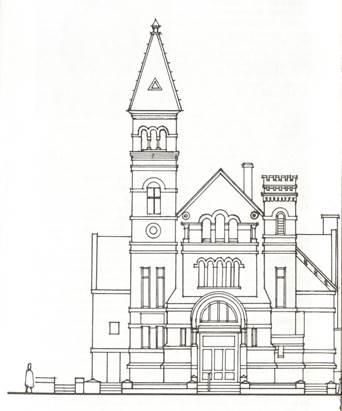

some attempts at advertising for building plans, the trustees again hired

Horatio White to design and oversee the building of the church, to be

constructed of Onondaga limestone on a lot at

The new church was

completed in the fall of 1885, a gray stone building of mixed Gothic and Romanesque

design with a black slate roof. The front of the building faced

______________________

*A box of memorabilia

sealed into the wall during the ceremony came to light again four generations

later and its contents are now in the church archives. As of this writing, the cornerstone itself rests in

the memorial garden of our present church building.

[page

21]

by

a spacious octagonal vestibule and side porches, all of which, including

auditorium and ceilings, are finished with western cherry lumber, high

wainscotings and paneled ceilings. The pews are constructed with cherry, in a

crescent form, the floor descending towards the pulpit thirty inches. The

rental capacity is 450 sittings, with ample accommodation for 500. The organ

and choir are located in a high arched niche over the pulpit."

The

inside roof and walls were braced with carved wooden trusses and steel rods

that stretched across the upper space of the auditorium. Five tall, arched

windows in each side wall were eventually filled with stained glass windows,

memorials to John Storer and lay men and women who had been devoted church

members.* One

hundred twelve pews filled the auditorium where center and two side aisles

led down to the dais and pulpit. Flanking the dais were panels lettered with

Bible verses under the headings "God Is Our Father" and "Christ

Is Our Teacher," and below each of these panels was a large fireplace and

mantel. Doors on either side led to Sunday school rooms, stairs, a parlor,

kitchen, and “other conveniences." In the basement were three furnaces

guaranteed to keep the rooms heated to 70 degrees in zero weather. They didn't,

and had to be replaced with four others a few years later. When

The

Music

was very important to this congregation. Each year one of the first duties of

the trustees was to appoint a music committee, which had more members than any

other standing committee. The church women regularly raised money for the music

fund, and in 1884 they also gave Mrs. Calthrop a Steinway grand piano with a

silver plaque. In the late 1880s the finances faltered again and yearly

deficits began to build up, but the congregation would not consent to trim the

$1,200 appropriated

______________________

*When the building was sold

eighty years later, photographs were taken of the windows. They are kept in the

church archives and displayed on

the church web site.

[page

22]

for

the organist and “choir," usually a paid quartet. When the trustees

suggested the church might have to close, the organist resigned and volunteers

had to supply the music. The next year the congregation voted to raise funds by

a special subscription to hire an organist and quartet and to enlarge the organ

loft to accommodate a chorus choir.

Economic

problems beset the whole country in the early 1890s. During the panic of 1893

members of the Unitarian society joined with others in the community to feed

the hungry, using city schools as distribution centers. Sam Calthrop stayed in

town to coordinate the effort and did not return to Primrose Hill until the

crisis was over. The previous year he and his daughters, with the Helping Hand

Guild Committee of the church, had started the Newsboys' Evening Home in the

Sunday school rooms. Youngsters could come several nights a week for cookies,

cocoa, classes, and games. The Boys' Home ran in the church for 10 years until

it could move to more appropriate quarters. The organization kept on growing

and is now known as the Syracuse Boys' Club.

The

Women's

At

this time two young women of the congregation were preparing for the Unitarian

ministry and both were ordained at May Memorial church. The first was Marie H.

Jenney, who was ordained in June 1898 and served as co-pastor with Rev. Mary

Safford in the

Young

women at the church were not the only ones overcoming traditions. At the annual

meeting in 1901 the congregation started a policy of electing members of the

Women's

[page

23]

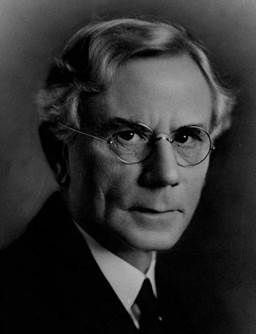

Rev. Dr.

Samuel R. Calthrop, third minister 1868-1911

presented

a new registry book to the congregation. This project had been proposed and

discussed for a decade. All

past members of the congregation were listed in the registry, with their

individual signatures if copies were available. Current members were invited to

add their signatures, and all new members since then. Long-time members recall

that signing the book has not always been expected of new members, but it is

today and the same registry book is still being used.

For

30 years Dr. Calthrop had preached without notes and his sermons were becoming

either too short or too long, because the trustees in 1897 requested that he

"prepare sermons of 30 minutes duration." He responded favorably and

also suggested the society hire an assistant. They did not have the funds to

pay another professional until 1901, when they decided to find an associate

minister. Albert W. Clark

of

[page

24]

unkindly

reported that although the congregation liked Mr. Clark, they had voted to have

sermons delivered only by Dr. Calthrop.

The

Sunday school grew under young

The

Women's

In

December 1909 three trustees called on Dr. Calthrop, then 80 years old, to

discuss church conditions. They reported at the next board meeting that it was

mutually agreed the time had come when a younger man should be secured to take

up the work of the church, with Dr. Calthrop as pastor emeritus. In January

1911 the Reverend John Henry Applebee, also English by birth but educated in

the

The

church was renovated and a new organ installed in a new choir loft at the back

of the auditorium. For several years afterward the public was invited to

regular organ recitals that were an important part of the church program. A

group of church ladies commissioned sculptor Gail Sherman Corbett to make a marble bust of Dr. Calthrop, and

two pedestals were ordered. The marble busts of May and Calthrop were placed in

the front of the sanctuary where they stood, white against the dark paneling

for the next 40 years.

At

the annual meeting of the congregation in January 1914 Dr. Calthrop, no longer

able to sit through a whole evening gave a parting blessing to the assembly and

said of Mr. Applebee, "...my good friend is

[page

25]

just

making things hum." In his annual report John Applebee explained a

social service plan worked out by the city and the churches, in which each

congregation assumed partial responsibility for social services in a specific

district. He asked the congregation to cooperate "to show our practical

religion of the brotherhood of all men." At about this time Applebee wrote

in his diary, "I have been here for three years and have just presided

over my first communion service. Since 1911 Dr. Calthrop as pastor emeritus has

preached once a month and taught a Sunday school class. This January, 1914, he

gracefully acquiesced in the opinion of his friends that he should be released

from all responsibility and work, owing to the necessary infirmities of

age."

At

the beginning of his fifth year at May Memorial, John Applebee reported to the

annual meeting that Sunday school attendance ranged from 70 to 130, the Women's

Alliance was strong, the Men's Club in a flourishing condition, and the Samuel

R. Calthrop League meeting regularly for play readings, lectures, and other

"instruction and profit." John Applebee, who was a slender five feet

eight inches, related that on his first visit to Syracuse his host, Samuel

Calthrop, had set him to sawing wood, and someone in an aside whispered

"he has been sawing wood ever since." With grateful enthusiasm

members at the meeting passed several resolutions thanking John and Alice

Applebee for their faithful work, warmth, and inspiration" under

conditions making any adequate financial recompense impossible." One year

later the trustees raised Applebee's salary to $3,000.

Samuel

Calthrop died in 1917 at the age of 86. Church member Salem Hyde wrote a

memorial in which the congregation expressed "... tenderest

affection... overwhelming gratitude toward the memory of our pastor and friend,

who has given us so much and given it so graciously and with such telling

effect on us and on the people of this community." Beside Mr. Applebee at

the funeral service were Rev. Frederick Betts of the Universalist church, Rabbi

Adolph Guttman of

And now may the peace of God that passeth

all understanding, keep our hearts and minds in the blessed knowledge that our

Father's love is eternal: may that love be ours; our guide through life; our joy in

death; and our glory throughout eternity. -- Amen.

[page

26]

100 YEARS AND BEYOND

World

War I brought

For

many years the Unitarian society had a tradition of holding a congregational

meeting in October to secure financial support for. the church. In the early years

of the society, a pew auction was held in October and a deed of

"ownership" was presented to each successful bidder. Later on, church

members voted at the October meeting to pay the cost of organist and choir

singers recommended by the music committee and, when auctions were abandoned,

they used the occasion to arrange their pew rentals for the coming year. By the

1900s the October meetings had become birthday celebrations for Sam Calthrop,

and Calthrop birthday dinners continued to be held for years after his death.

The Calthrop birthday anniversary dinner of

During

the years before and after World War I, joint services were held with the

Universalists and

The

women of the church were traditionally represented by two females on the Board

of Trustees, but in 1918 Mrs. F. R. Hazard was elected a third woman trustee.

In nominating her at the congregation's

[page

27]

annual

meeting, George Cheney noted that it was a departure from precedent, but

"the world turns and we have come upon a new time. Woman suffrage has

triumphantly carried the State of

The

turmoil and social changes of the 1920s are only vaguely reflected in the

church records. At a time when evangelist Billy Sunday was attracting hundreds

to the traditional Protestant churches, the Unitarians, who had bought a movie

projector for the Army Club, invited the public to weekly movie shows. In 1923

the congregation sponsored a week-long mission service that featured a visiting

Unitarian minister. At least one family we know joined May Memorial in reaction

to Billy Sunday and that was Joyce Ball's family, the DeLines.

In 1922 attendance at May Memorial averaged about 130 and there were 43

children and seven teachers in the Sunday school. The church school director

was Elizabeth Lewis who became one of the first members to receive the Annual

Award when it was started in the mid-1950s. Our records describe a church

meeting in 1925 when the congregation discussed reviving the communion

ceremony, which had not been held “for some time," as part of the Easter

service. Implementation was turned over to the trustees who decided on a simple

memorial communion service to be held on Palm Sunday. Our older members can

remember communion held in the church on some occasions after that, but the

practice had disappeared by the 1950s.

Once

again in the late 1920s the church was faced with dwindling membership and a

beloved elderly minister who no longer filled the pews on Sunday. Dr. Applebee

(DD Meadville, 1924) twice offered to resign, but the congregation was very

fond of their saintly pastor. They voted to keep him as minister and hired a

part-time secretary to assist him with writing and mailing the church

newsletter from his home on

Rev.

Evans A. Worthley was interim minister until the

congregation,

[page

28]

Rev. Dr. John H. Applebee,

1911-1929 Rev. Dr. W. W. W. Argow,

1930-1941

called a

dynamic new minister, W. W. W.

Argow, a former Baptist who became a pacifist and joined the Unitarian

denomination. He came to

In

spite of all this activity, the church finances were precarious, with deficits

depleting reserves and Dr. Argow turning back part of his salary every year.

The church tried to help with the problems of the Great Depression by opening

its Sunday school space as a reading room for unemployed people who were

walking the streets. An average of 75 men used the reading room every day it

was open during 1931 and 1932.

To

raise money for the church budget the Laymen's League sponsored lectures by the

famous minister John Haynes Holmes. The Women's

[page

29]

at

the art museum. They also sponsored plays for children put on by the Clare Tree

Major road company, and held garden parties at the home of Judge and Mrs.

Hiscock on

The

big event of the decade was the one hundredth anniversary of the society

celebrated by a week of activities in October 1938. Centennial events started

with the Sunday service on 16 October led by Dr. Argow who spoke about the "Challenge of an

Inheritance." He was assisted by church member Rev. Elizabeth Padgham, now

retired and living in

In

December 1939 May Memorial invited the congregation of

Dr.

Elizabeth Manwell, a teacher of child development at

[page

30]

and

author of several books, some in collaboration with Sophia Lyon Fahs, a well-known Unitarian writer and educator. Manwell's book "Consider the Children, How They

Grow" was an important addition to parent education and won an honorable

mention from Parents Magazine in 1940.

Dr.

Reginald Manwell,

In

October 1940 the congregation bought the home of the Van Duyn

family who had lived next door. The building was of special interest to

Unitarians because it had housed the first family relations clinic, a precursor

of Planned Parenthood and a controversial facility that many church members

supported. A woman most instrumental in the success of the clinic was Sarah

Hazard Knapp, daughter of Dora Hazard and mother of our long-time member, Sarah

Auchincloss. The asking price of $5,000 was paid in

cash thanks to a legacy left by Anna Agan Chase.

Volunteers raised money, remodeled, redecorated, and the church school moved

into the parish house soon after the New Year. Dr. Argow called the

congregation together on

The

1940s challenged the social consciences of religious liberals more than any

time since the Civil War. During the next dozen years, two ministers came and

went at May Memorial. Both were youthful and conscientious men who ultimately

felt a call to duty more challenging than the needs of a comfortable,

middle-class congregation. The majority of Unitarians at May Memorial seemed

very conservative to liberal clergymen, although the members themselves

considered their church a bastion of liberalism in a conservative community.

Rev.

Robert Eldon Romig came to the pulpit at May Memorial in the summer of 1941.

Because of the wartime housing shortage Bob and Ellen Romig could not find a

suitable home, and the church bought a parsonage for them, a large colonial

house on

[page

31]

Dr. Elizabeth Manwell

DRE 1936-1949

96

the year before. In 1944 Romig worked for the United War Fund, organizing five

In

spite of the pacifist sympathies of its ministers and some members, most of the

young men who grew up at May Memorial went into the service when the United States

entered World War II, and many of them were killed. The honor roll for both

world wars is preserved in the church archives. The women of the congregation

concentrated their war efforts in two directions, sewing for refugees, and

serving lunches to school children whose mothers were working full-time. In

1943 Alice Southwick and Dorothy Wertheimer organized volunteer women from the

church, the neighborhood, and the university. Each volunteer came in one day a

week to help cook and serve lunch to the children. The project grew to involve

about 70 volunteers a week serving from 50 to 60 lunches daily. By the end of

June 1945 the women had served 8,500 lunches! When the war ended, the women

turned to collecting and packing food and clothing for European relief. In

December 1945 they shipped 118 boxes of food and in 1947 a similar number of

boxes of clothing was packed and sent to

Rev.

Glenn Owen Canfield came to May Memorial in the fall of 1946,

[page

32]

May

1884-1964

May Memorial

Parish House,

1940-1964

(next door

to church connected by a corridor)

[page

33]

determined

to open the congregation to more liberal ideas. He had become a Unitarian in

1943 after ten years as a Presbyterian minister in the midwest.

During his

When

Elizabeth Manwell retired in 1949 the congregation celebrated her work at May

Memorial and throughout the denomination with a dinner. At the same time they

welcomed Josephine Gould as the new director of the church school to which she

had contributed much knowledge and experience over the years. She was already

well known for her work and publications in the religious education field.

Church

membership was increasing. Canfield attracted a strong young

[page

34]

Rev. Robert E. Romig, 1941-1946 Rev. Glenn O. Canfield, 1946-1952

adult

group though his campus ministry and, with the help of newspaper ads inviting

the public to "come and think," membership at May Memorial increased

to 400, the largest in its history.

In

September 1951 the congregation held a dinner to celebrate the fiftieth

anniversary of Elizabeth Padgham's ordination. Glenn Canfield spoke of the

service she gave to her home church during her retirement. In the fall of 1952

Glenn Canfield and his wife Ellen left

With

its large, active congregation and its excellent church school program, May

Memorial was one of the strongest churches in the denomination. At least one

denominational official warned of a conservative bloc in the congregation.

"The minister who goes there will have to trim his sails considerably and

with some strategy may be able to keep the liberal gains that Glenn Canfield

has made," wrote Dale DeWitt of AUA. He praised the "splendid

people" in the church even as he expressed doubt that a social emphasis

program could be achieved at May Memorial. The pulpit committee soon presented

two excellent candidates who visited the society to give candidating

sermons. In a congregational meeting the members voted to call the one

recommended by the pulpit committee. It was a close vote, which left the winner

with some disappointed parishioners to win over, although he received a

unanimous vote of confidence once the election was official. The congregation

had chosen the Reverend Robert

L. Zoerheide from

[page

35]

GROWTH, FORM, MOVEMENT

When

Bob Zoerheide came to May Memorial, no one foresaw the tremendous changes that

would accompany his ministry. He was a tall, youthful man with a quietly

deliberate manner. Theology and personal religion were important themes of his

sermons. He spoke about individualism, variations in Unitarian thought,

Biblical scholarship, the Dead Sea Scrolls and the new philosophy of

existentialism. He did not neglect social problems. He served on the board of

NAACP, he supported civil rights and housing, but the closest he came to activism

was to speak out on church-state issues such as religious instruction in

schools and loyalty oaths for teachers and other public employees.

Almost

as soon as he arrived, Bob Zoerheide found himself drawn into a controversy

regarding the Council of Churches. The Syracuse Council of Churches had been

formed by the Protestant Christian churches, including the Unitarians and

Universalists, in 1931. Both the Unitarian and Universalist ministers had been

active in the council ever since, serving as officers and board members of the

organization. May Memorial trustees annually appointed lay members to serve on

boards and committees of the council. When the National Council of Churches

reorganized in 1945, it required member congregations to declare acceptance of

Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior, but the local council did not adopt the

statement as a membership test.

Gradually,

before and during the war years, the majority of Unitarians let go their

traditional ties to Christianity in favor of a commitment to broader religious

values. By the time Bob Zoerheide arrived here at the height of the McCarthy

era, when "liberal" was a popular euphemism for

"communist," many traditional Christians were becoming very uneasy

with their liberal religious brethren. Because of the Christian emphasis, some

members of May Memorial pushed for the congregation to dissociate itself from

the Syracuse Council of Churches. This attitude grew stronger when the majority

of the Protestant churches sponsored a campaign in

It

was not a good time to break with the Protestant community. During those

midcentury years a struggle was going on about state aid to parochial schools

and released time in the public schools for the purpose

[page

36]

of

religious instruction. These programs were considered violations of the

constitutional principle of the separation of church and state, and the AUA had

protested against them through resolutions passed by delegates at the

denominational May Meetings. Unitarians and Universalists in

Plans

for a liberal religious coalition in

[page

37]

Rev. Robert

L. Zoerheide

Minister

from 1952 to 1961

work

on arrangements and hospitality. The Hotel Syracuse staff was cooperative but

confused. They are said to have directed arriving Unitarian delegates to a

meeting of "Ukrainians" on the tenth floor. Telephone communication

kept each conference informed about the other's deliberations as the two groups

considered separately the Commission recommendations.

Of

course there were difficulties. Rev. Max Kapp, Dean

of St. Lawrence Theological School, quipped that the Universalists were afraid

of being swallowed by the larger Unitarian denomination, while the Unitarians

feared they would get indigestion. When the two groups were near agreement they

met in joint sessions at the Syracuse War Memorial auditorium to discuss and

vote on identical recommendations. They argued about whether to include the

name "Jesus" and other "great prophets," and finally

resolved the issue by leaving out names and referring to the

"Judeo-Christian heritage." Delegates voted to combine the national

organizations of the two denominations into one that would be called the

Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA). They proposed a constitution that

would be approved by both denominations at their last national conventions in

1960.

Credit

for the success of the merger meetings was largely due to the friendly manner

and parliamentary skills of moderator Ralph Kharas, a

member of May Memorial and Dean of Syracuse University Law School. After the

conference, he is said to have confided to friends, "I wasn't always

exactly sure of the proper ruling, but I made quick decisions and when I banged

the gavel no one objected."

The

merger in no way affected the independence of individual congregations, who

were left to decide for themselves whether they wanted to change their names or

join with others. Congregations all over the country were asked to approve the

merger plan before it could be implemented. In January the congregation at May

Memorial voted for it 85 to 1. Relations between May Memorial and the Syracuse

Universalist church remained cordial and each congregation continued on its

traditional way after the denominations united.

[page

38]

The

May Memorial tradition of offering use of the church building to community

groups helped start several local institutions. One of them was the

The

hard times of the thirties and the grim years of war and refugees were gone,

but the society had a new problem, overcrowding. Young suburban families filled

the two buildings every Sunday and their automobiles lined both sides of the

surrounding streets. The church school exceeded its capacity with 180 pupils

and more came every year. The church rented rooms in the

The

trustees launched an expansion fund drive in October 1956 and appointed a site

committee that scoured the city for suitable property without success. At the

trustees meeting in December they were tired and ready to abandon the idea of

moving, but Bob Zoerheide persuaded them to reorganize their committees and

keep on looking. In March 1957 the congregation reaffirmed the decision to

relocate by a vote of 107 to 10 and authorized the board of trustees to take

any action necessary to implement it. Several months later the site committee

found the property

[page

39]

they

were looking for and the congregation passed a motion to buy it. With the

acquisition of land at the corner of

Disappointments

dogged the relocation process.

At

the annual meeting in June 1960 Bob Zoerheide described an informal survey of

U-U churches that placed May Memorial near the top nationally in overall

membership, size and excellence of church school, budget, and support of the

denomination. During his ministry membership had grown to more than 500, and

the annual budget had grown from $14,000 to $34,000. There were three active

youth groups in the church, a part-time paid youth director and a large campus

club of Unitarian youth who met several times a month at Hendricks Chapel. A

program council of representatives from all congregational groups met regularly

to coordinate church activities and report to the trustees. An active

membership committee greeted visitors and planned meetings and social events

for interested newcomers. The trustees accepted the names of new people into

membership by formal action at board meetings, and new members kept coming.

Such

a vital congregation could not allow itself to be discouraged. In the fall of

1960 the board of trustees under president John Chamberlin started a new

capital fund drive and appointed three new committees to develop alternative

plans for the future: long range, staying at

Besides

the increased membership, the church had changed in other ways during Bob Zoerheide's ministry. An all-volunteer choir had replaced

the paid quartet; young parents could bring their infants and

[page

40]

toddlers

for child care while they participated in adult activities or taught in the

church school; and the life-size marble patriarchs that had flanked the pulpit

for so long were moved first to the vestibule, and then out of sight entirely

to a history room in the small front tower. Most importantly, the society had a

new site and a good start on a building fund, although they still had no

architect.

Another

congregational vote in April 1961 reaffirmed the members' determination to

relocate. They voted 145 to 95 to build at 3800

At

the same time, the pulpit committee had been looking for a minister. At a

congregational meeting in June 1961 members voted unanimously to call the Reverend John Channing Fuller

from Orlando, Florida to be the next minister of May Memorial.

John

and Betsy Fuller settled in

[page

41]

growth,

and movement, is fundamental to Unitarian belief." They asked for architecture

marked by beauty, dignity, serenity, strength, stimulation, and challenge. And

they engaged the best acoustical consultant and most expert organ builder

available.

At

the annual meeting in 1963 the treasurer announced a new high in annual income,

$51,000. Henry Mertens reported that the final building plans would be let out

for bids that summer. In September the congregation voted 100 to 10 to hire Kosoff Construction Company and construction started a few

weeks later. Although sale of the

Building

plans were not the only congregational concerns. More families were joining and

the church school registered 300 children in 1962 and 1963. Bob Burdick

organized a group of parents to keep a fire watch patrol in the parish house

during church school sessions because the building was considered unsafe. A

special donation funding Sunday morning care for infants and toddlers ran out

and a decision had to be made whether to continue it. Elizabeth Manwell and Jo

Gould opposed having the young parents' cooperative babyfold because they

believed nursery care was detrimental for children under the age of three. The

trustees studied the question and decided to support the babyfold separately

from the church school.

Meanwhile

John Fuller was not neglecting the social problems of

Standing

in the carved mahogany pulpit above one side of the dais, John Fuller could

look down through a decorative ironwork grill in the floor into the furnace in

the basement below. In the winter time he joked that he only had to lean over

to see the fires of hell. He did not need this view to remind him to address

the "burning issues" of the day. In addition to his own interests in

liberal causes, activist members of the congregation were enthusiastic

supporters of black protests against urban renewal programs in the center of

[page

42]

counter

discrimination that made it difficult for displaced black families to find

affordable housing in other parts of the city, John Fuller and Elizabeth

Manwell formed a May Memorial committee that worked with other organizations

helping displaced families find housing. These developments disturbed church

members who felt the proper concern of the Unitarian Society was basic moral

and philosophical discussion, with social action to be left to the discretion

of each individual, not to involve the congregation as a whole. This was not a

new conflict, only new to the generation that encountered it for the first

time.

When

a new Public Affairs Committee formed, the trustees monitored it carefully,

requiring it to report to the board before taking any public action. The board

allowed the committee to organize a community-wide forum on discrimination in

housing and to lobby City Hall for practical measures to increase low-income

housing. After several informational meetings, six resolutions urging the

Syracuse Housing Authority and the city administration to take action were

presented to a formal meeting of the society for a vote in March 1965. They

were passed by standing vote and for the first time the congregation itself

spoke out publicly on a social issue.

In

1965 the committee issued an informative study, "Scattered Site Public

Housing for

During

these years the Sunday morning forum was a regular and popular part of the

church program that was ready-made for presenting public issues to the

congregation. Church school started at

[page

43]

Syracuse

Memorial Society, a nonprofit organization that assists its members to make

reasonably priced arrangements before they die. Henry Schmitz presided over the

group for a decade.

In

the winter of 1964 the new building was going well, but there was unrest in the

congregation. Because of the capital fund drive there had been no regular

canvass for three years, and canvassers in the fall of 1963 had found a lack of

enthusiasm for new pledges. President Warren Walsh complained of fragmentation

within the society, church school attendance was dropping and in January John

Fuller was hospitalized for exhaustion. This was the first outward sign of the

heart ailment that was to plague him for the next ten years until his untimely

death in 1974. Besides his work as minister of a large congregation he worked

on three committees for the UUA and several local community boards and

committees. After several weeks' leave he started back to work gradually and in

May he returned to a regular 5˝ day work week, without so much committee

responsibility.

The

new building was to be ready in the fall of 1964 at a total cost of $446,391.

To meet this cost the society borrowed $180,000 to be repaid over 30 years with

mortgage payments totaling nearly $12,000 a year. At the annual meeting in the

spring of 1964, despite the net loss of 20 members during the past year, the

finance committee reported another record amount in pledges, $52,000. In

September a $75,000 offer for the

On

[page

44]

MAY MEMORIAL UNITARIAN SOCIETY

Saturday

and Sunday, 28 and 29 September 1964 were moving days for May Memorial, with no

services scheduled. Committees inventoried the furnishings at

The

architects and builders did their work well. There is an openness and serenity

about the wide auditorium that invites members of the audience to look toward

each other as well as toward the speaker in front. There is no pulpit, only a

simple, movable lectern of wrought

iron and wood designed by artist Dorothy Riester.

Instead of a dais, there is a wide

stage three steps above the auditorium floor. At the back of the stage a

fourth step leads up to the backdrop, a wooden partition with a long shelf for

decorating. The warm glow of the natural stained cedar walls is set off by dark

crossbeams at regular intervals. On either side of the platform massive demiarches carry the eye upward, past the clear glass

windows above the walls, up to the cedar paneled ceiling and the square cupola centered atop the

gently sloping roof. On sunny mornings the dark wood behind the minister is

lighted by an image like a butterfly (or an angel?) shining down from the

cupola and moving gradually down the wall and across the floor as the earth

turns toward the sun.

With

his first sermon in the new building, John Fuller set the relocation in the

context of liberal religion. It was not the inadequacy of the old building

alone that moved us, he said, but "an urge, a restlessness to bear witness

to our own time and to the vision of what we seek to be and to become... this

is the essence of liberal religion -- to fashion our own world, our own

insights, our own manifestations of truth and beauty and goodness."

In

this spirit of fashioning their own society, members gathered after the service

the next Sunday to discuss whether the name May Memorial should be kept or

discarded. Many of them knew little or nothing about Samuel Joseph May and they

associated the name with the stone towers at

[page

45]

May Memorial

Unitarian Society,

do

with the spirit and purpose of the congregation that occupied it. When they

heard about May's concern for the rights of blacks and women and the right of

all children to a good education, many felt that his agenda was completely

appropriate for the 1960 s. But they did not have time to reach a formal

consensus. One of the speakers at the forum was Elizabeth Manwell who had come

to take part even though she knew that her heart disease was becoming critical.

A few minutes after making a passionate plea for keeping May's name and

carrying on his work, she sighed and collapsed in the lap of long-time member Mary Cooper, whose great uncle

James Bagg had first suggested the name May Memorial

Church. Immediate attention from doctors present could not save

The

name "May" has another significance for

long-time members because of the years that May Slagle served as church

secretary. In the minds of many church school children who heard their parents

mention May Slagle, she, not the minister from 100 years ago, was the source of

the church name. Mrs. Slagle had been one of the most active volunteers in the

school lunch program during World War II, and her joy in cooking for children

was renewed every year at the Easter breakfast she prepared for the children

who came to rehearse the Easter pageant. As the school became larger and the

Easter pageant was dropped, she invited only the first and second graders to

breakfast. They put on stiff paper rabbit ears with pink linings, ate scrambled

eggs and played games in the church dining room on the Saturday before Easter.

In the eyes of most adult members, May Slagle was the indispensable office

manager. She had

[page

46]

been

a part of the church for many years, as editor of the newsletter with Mr.

Canfield and office secretary with Bob Zoerheide. After the move to the new

building she worked as minister's secretary, parish assistant and hostess in

charge of building security until she retired in 1974. Another strong

member/employee who kept the society functioning was treasurer Alice Jordan.

She started working as assistant treasurer in the mid-1930s. A small, quiet,

friendly person, she kept the books in order until her death in 1970.

All

the staff and most of the congregation settled joyfully into the new building,

but the move brought many other changes. For the first time in the history of

this congregation a woman, Verah Johnson, was elected president at the annual

meeting in the spring of 1965. When church reopened in September the long-

standing

The

formal dedication of the new building was held on

In

spite of a large membership and active congregation, the trustees in charge of

the church finances were troubled. Mortgage payments amounting to nearly one

fourth of the church budget were a tremendous burden and the church was facing

larger deficits every year. At the annual meeting in June 1966 the members

heard about a great many activities, but a widespread failure to support the

economic needs of the

[page

47]

Rev. John C.

Fuller, minister

From 1961 to

1973.

society.

Church expenses stayed within budgeted figures, but pledges were falling

behind, and new expenses were anticipated. Jo Gould asked to limit her

responsibilities to supervision of the lower grades in the church school, and

the new Youth Education Committee called for an assistant minister to help with

the young people. John Fuller had already expressed a need for an assistant to

help him minister to the large congregation. In November, Fuller again went to

the hospital for a complete rest. Jo Gould requested a paid assistant, but the

society could not afford it and the trustees refused to charge a fee for pupils

in the church school. In 1967 the UUA began formal accreditation for Directors

of Religious Education and Jo Gould was one of the few who qualified for the

DRE without additional study and training. She was honored for her new

professional status at May Memorial's annual meeting in June. A few months

later Jo resigned as DRE at May Memorial effective June 1968, after which she

took a position at the First Universalist Society where the Sunday school had

fewer children. Her resignation, plus another hospitalization for John Fuller

at Easter 1968, brought to a head the need for an assistant minister. After a

series of neighborhood group meetings to discuss the situation, the trustees

appointed a search committee that recommended a minister. from a new fellowship

in the midwest. He decided not to accept the call and

the church then called Ronald Clark

from Berkeley, California, who was appointed DRE in June 1968.

In

the fall John Fuller, back in the pulpit after a restful summer, reported to

the trustees that everything was going smoothly with the two ministers. The

treasurer reported the church was still running a deficit, but it was less than

expected. At Fuller's suggestion the trustees decided to make the call for financial

support less strident by eliminating the offering from the morning service and

attaching the collection plates to the sanctuary doors where the congregation

members could drop their offerings as they walked out after the service. This

experiment was continued for two years, although it cut nearly in half the

amount collected every Sunday. Early in 1970, in view of continuing deficits,

the congregation voted to reinstate passing the plate for an offering during

[page

48]

Mrs.

Josephine T. Gould, Directory of Religious Education,

1949-1965

the

Sunday service, for an estimated $900 increase in yearly income.

At

the annual meeting in June 1969 John Fuller described the congregation as

swinging. The Samuel J. May citation had been instituted in 1967 to honor

political and social action, and the first one had been presented to Eleanor Rosebrugh, a long-time member who was a social worker and

journalist as well as a strong supporter of social action within the

congregation. In 1969 the citation was given to Mr. and Mrs. W. D. Rumsey, a

This

was the era of the War on Poverty, the sexual revolution, burning ghettos,

student protests, and antiwar demonstrations. Under John

[page

49]

Fuller's

leadership many members of the congregation took an active part in the Civil Rights

struggle and the anti-Vietnam War effort. Like many other U-U ministers, John

Fuller counseled conscientious objectors and women seeking legal abortions

outside

The

UUA was involved in many of the controversial issues and the national board

voted to fund the Black Caucus, an organization of Unitarian blacks who wanted

to use denominational funds to help start businesses in black ghettos. As a

result the denomination lost a lot of members and support nationwide. In

desperation the UUA Board suggested mandatory assessments on congregations to

support the denomination's budget. In 1969 the May Memorial congregation voted

against mandatory assessments by the UUA, and the trustees broke the long and

continuing tradition of sending uninstructed delegates to General Assemblies by

instructing delegates to vote against the mandatory assessments. Money was so

tight in the denomination that the St. Lawrence District had to give up its

offices and for a while operated out of the Goulds'

house, where Jo acted as secretary.

Even

with its serious financial problems May Memorial was still considered one of

the healthiest congregations in the denomination because of its large and

enthusiastic membership. During the 1969-1970 church year the trustees met

weekly to try to solve the deficit problem, which was expected to reach $10,000

by June. The society raised money with a series of roast beef dinners, cooked

by John Fuller, that were open the public, and put on a large and successful

May Faire.

Successful

fund raising staved off disaster, and the trustees encouraged a wealth of

activities to try to alleviate divisive resentments and factionalism among

members. May Memorial was a bustling place where some members were deeply

involved in encounter and discussion groups. The trustees established the

Gallery Committee to mount museum quality shows by local artists in the social

hall. When Ron Clark resigned to accept a call to a pulpit in

[page

50]

pulpit

on Sundays. In May the trustees established the campus intern program in

cooperation with the First Universalist Society, to provide living expenses for

a U-U ministerial student who would work at Hendricks Chapel of Syracuse

University. At the annual meeting that June total pledges of $59,000 were

reported, and receipts exceeded expenses for the first half of the year. John

Fuller said the society was in the "... healthiest condition since he came

in 1961."

In

less than a decade, May Memorial had weathered the move to a new building with

the ensuing financial difficulties, and a tremendous turnover in membership. At

the annual meeting in 1972 John Fuller reported that there had been 800 new

members in ten years, with a net increase in membership of zero. Although he

described the current status of the society in the words of a popular

psychology book of the day, "I'm OK, You're OK," his health continued

to be a problem. Without his strong leadership attendance dwindled and deficits

built up. After a series of discussion meetings among the members about the

goals and needs of the society, Fuller resigned in the spring of 1973 and

accepted the call of a smaller congregation in

With

John Fuller's death Unitarian-Universalists lost "one of the very rare

men" known for strong leadership in the denomination, an assessment made

in 1964 by Dr. Duncan Howlett of the All Souls'

pulpit in Washington, D.C. Fuller had steered May Memorial during its own

relocation and the changes of the black revolution, women's movement, including

the demise of the local Women's Alliance, and the Vietnam war protests with

their peace marches and teach-ins. He had personally played a vital part in the

great movements of that time, leading local ministers into dialogue with City

Hall over discrimination, taking part in protest marches and teach-ins,

supporting activism within his congregation for housing, jobs, and peace. True

to his own words; he had fashioned at May Memorial a "sanctuary of every

seeking, questing soul…an open door to all truth and all men." Members of

the congregation traveled to

[page

51]

OPEN CHANNELS

The

fortunes of May Memorial Unitarian Society were at a low point that summer of

1973, but a nucleus of dedicated members hoped the congregation would grow

again and worked to make it happen. They called interim minister Rev. Robert Holmes

to the pulpit for the 1973-1974 church year and, with

the help of the UUA, organized a search committee to find a successor to John

Fuller. Late in April 1974 the committee recommended a man "very nearly